Character Study: A Guide to GAME OF THRONES Scripts in the WGF Library

By Lauren O’Connor

From sitcoms to cable dramas to procedurals, television shows succeed based on our emotional engagement with one critical thing: characters. You can’t even say the word “character” without saying the words “care” and “actor.” Without our deep interest in one or more of these fictional persons and their actions, we have almost no investment in a story. Without characters, plot becomes simply an unmotivated string of events.

As Aristotle famously said in his Poetics, “Poetry tends to express the universal, history the particular.” In drama, then, characters are relatable stand-ins for us. From them, we learn more about our universal human nature. Their needs become our needs. We feel catharsis as they rise, collapse, lose pieces of themselves, bend, and transform in pursuit of their purpose. Through watching them (and through writing them), we define what it means to be alive, to be a person.

I mention the essential-ness of characters as a lead-in to this blog post about our current favorite topic of discussion: Game of Thrones.

Express your intense feelings about the series’ conclusion all you want. I’m here to make the argument that the reason you possess intense feelings of any sort—the reason we’ve all been possessed with a collective passion and need to discuss the show at great length—comes down to that one critical thing: the way the storytellers made us feel about Sansa Stark, Tormund Giantsbane, Cersei Lannister and the rest of the characters.

The conclusion of any epic tale is a great excuse to dive in for deeper analysis. If you’re feeling a lot of feelings at the conclusion of GoT, this post is meant to offer you some suggestions and tools for how to mine those emotions that were stirred in you and make them an active part of your own writing and character development process.

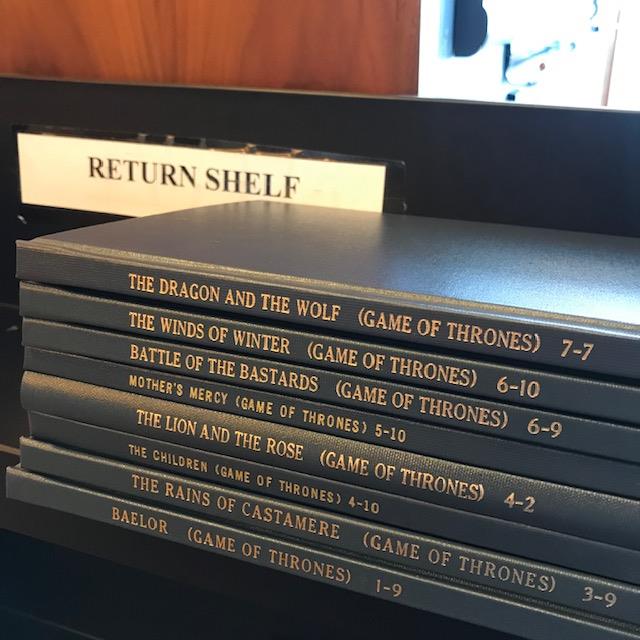

The WGF Library is home to most of the Game of Thrones scripts. Donated generously by D.B Weiss, David Benioff and HBO, they are an incredible educational resource for any writer looking to better their skills. Those who can visit our library in Los Angeles have access to pages upon pages of fire, blood, sweat, tears and literal years of grueling work.

If you’re a writer, I probably don’t need to tell you that one of the single best ways to develop your story sense and abilities is to read the work of other writers—to note what they do on the page to elicit certain feelings in you. To this end, the GoT scripts are one of the best learning resources around.

Part of what makes Game of Thrones wonderful is its hybrid nature. Included on the WGA’s list of 101 Best Written TV Shows in 2013, the show, then in its third season, was lauded for adapting George R.R. Martin’s beloved novels into a pastiche of medieval fantasy, zombies, geopolitical intrigue, Shakespearean tragedy and more—the likes of which had never been seen on small screens. With so many elements on the table, where does one even begin when sitting down to study the scripts?

Given my lack of expertise in most other areas, I’m going to continue to make the case that while it’s the blending of different genres and ideas that make GoT feel unprecedented, it’s the relationship we forged with its ensemble of great characters that truly grabbed us by the throat, moved us, and kept us sticking around for more. It’s this ability—the character muscle—that is most worth understanding and using in your own work.

Game of Thrones scripts are chock full of tactics for presenting characters on the page in a fascinating, surprising and empathetic way.

Now, before we go any further, I should warn you that the rest of this post assumes a basic level of familiarity with Game of Thrones the TV series. If you haven’t watched it yet and are planning to, turn back now as i don’t want to spoil anything for you.

ESTABLISHING GOLIATH

Before we dive into the nuances of any one specific script, let’s set the table. As many have asserted, one of the central questions behind both George R.R. Martin’s books and the television series is the question of: Who deserves power?

This is a universal question that we’re faced with pretty much every single day—at work, in politics, in our families, in our relationships, in society. Who holds power and who deserves power?

One of the first things that Martin’s books and the subsequent television series presents is an object associated with almost absolute power. As J.R.R. Tolkien created a ring of power, Martin develops a throne of power. The person who sits on the throne holds the fate of pretty much everybody in their all-powerful clutches. More than this, it’s been a while since there’s been a truly good leader sitting on that throne. At the beginning of the story, once King Robert is killed, we’re presented with King Joffrey.

Indeed, all around the Seven Kingdoms of Westeros, there seems to be mass corruption stemming from that seat of power and, to complicate things, winter is coming.

It’s a feeling we can relate to just a little too well. The story melds this feeling into more than just a universal question. It presents us with a universal need. We want to see David slay Goliath. We want a Prince who was promised. We want the right person to be sitting on that throne. Because it parallels real life, the need is all the more urgent.

I note this because it illustrates how presenting a very important need to be resolved automatically generates emotional interest in the characters who will then populate the story. Because we want the right person to be sitting on that throne, we spend the entirety of GoT in search of the diamond in the rough who will be the leader the country needs. Who deserves the power?

And now the horse race begins…

MEETING OUR CONTENDERS

I think part of the reason GoT inspires such passion among its fans is because it’s like watching a horse race. We start to bet on certain contenders—contenders whose experiences we feel for, whose resilience in the face of enormous obstacles is aspirational, and whose values somewhat align with our own. We pick our favorites and hope for them to prove themselves and place. Like most great characters, they come to stand for us.

The characters who become central contenders for the throne are outcasts and outliers who begin the story hugely disadvantaged. (Note: We LOVE to root for a disadvantaged, isolated outcast.) The three people we really start to follow through the story are a bastard, a dwarf, and an exiled princess, all of whom are the black sheep of their noble families and all of whom struggle to transcend their stations in life.

As its narrative plays out, the story cleverly discards obvious heroes, leaving our primary and supporting underdogs more opportunity to rise to the occasion. The bloody, horrifying way that presumed heroes are discarded gives our remaining characters further fuel to step up, seek justice and make things right. To win.

One trick that Martin and the TV writers use to create engrossing characters is the subversion of established archetypes. They know the images and tropes of the fantasy genre, especially as they pertain to character—chivalrous knights, powerful kings with tragic flaws, damsels in distress, dragons—and they purposely flip them on their heads. It’s exciting because it’s new, yes, but it also makes the characters themselves feel different and further isolated because they don’t fit societal expectations (Turns out Westerosi society isn’t that much different from our own). This, in turn, makes us identify with them even more.

We cheer extra hard for the lady knight, the exiled princess who becomes a ruthless dragon-riding warlord, the smooth-swording bastard with qualities of an ingenue, the mean fighter with burn scars all over his face who’s actually a protective surrogate dad, the drunk queen who has more in common with Macbeth than Lady Macbeth, and the dwarf—called a monster and an imp—whose empathy and wit make him a huge power player in the game. We get behind all of them the way we get behind characters in, say, a Disney movie. We wait for them to turn their greatest liabilities into their greatest assets.

Now that we’ve established that the struggle for the Iron Throne (and control of the Seven Kingdoms) is a race with lots of contenders, let’s look at how the TV writers get us to fall in love with, root for, and place our bets on certain parties. By making us root for (or against) certain characters, the writers ensure that we stay tuned in until the bitter end.

CONNECTIONS

The best way for an audience to get to know an outcasted character who doesn’t have many friends or allies is to provide them with a buddy or two to whom they can reveal their thoughts and feelings. Sidekicks act as our direct portal into the story, so we can converse with the heroes. Every Prince Hal needs a Falstaff. Every Batman needs a Robin. In the case of Game of Thrones the television series (as opposed to the novels), this is particularly essential because characters don’t narrate chapters for us, but we still need to know what they’re thinking.

They’re allies. Daenerys talks to Jorah. Jon talks to Sam. Arya talks to the Hound. Brienne talks to Podrick. When characters reveal themselves to their buddies, it helps us to relate to them more. It helps us root for them more.

And in the case of subverting archetypes, especially in the cases of Daenerys, Arya and Brienne, it’s particularly fun to see hardened, stolid women in the fighter roles with drunk, bumbling advisors or squires by their side. It’s real wish-fulfillment for girls who studied Shakespeare and never got to see themselves in the leading King/Warrior role.

The writers also know how to imply a connection between two characters without even putting it in the dialogue. I’m including this small excerpt from “The Children,” episode 4-10, written by David Benioff & D.B. Weiss, wherein tomboy Arya meets the armor-clad Brienne in the Vale. Note how the simple reprise of one word connotes a similarity between the two women. This is a trick for writing with economy:

MONOLOGUES

Game of Thrones also uses a convention of the theatre to help us get to know its characters: the monologue. In the wrong hands, a two-page monologue can feel dry and boring, a lazy, on-the-nose shortcut for having a character tell us exactly how they feel. On Game of Thrones, monologues are active, meaning whenever a character gives one, it’s typically as courageous an action as taking an arrow to the heart on a battlefield. In a world that puts such a high premium on strength and power, making the choice to be vulnerable and admit fallibility is a hugely risky and courageous decision.

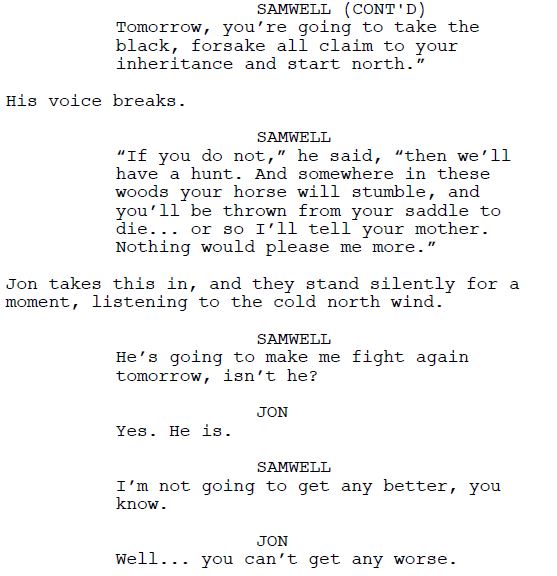

On a show like this, admitting your fears or secrets to another person is the ultimate gesture of trust and often the first step toward meaningful friendship. It’s an important lesson for any writer. When a character confesses something painful or difficult, it causes the listening character (and us the audience) to relate and get on board. Read this monologue from Samwell Tarley in “Cripples, Bastards and Broken Things,” episode 1-4, written by Bryan Cogman. After hearing Sam’s speech, we related and want to be his friend, just as Jon Snow does.

A CONDITION HAS NO NAME

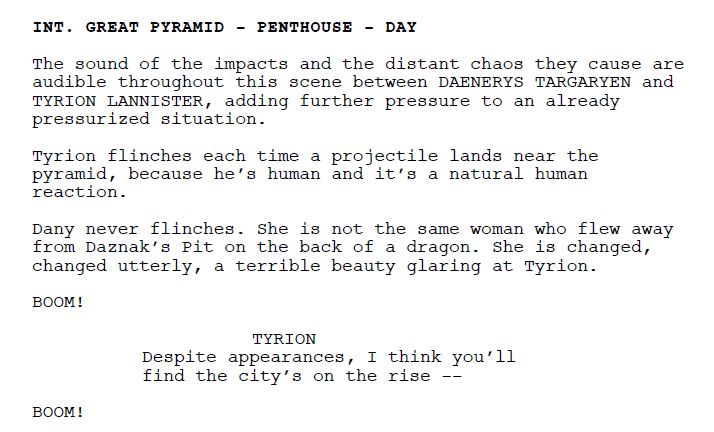

Let’s move in the opposite direction of monologues. One of the most common adages in any screenwriting book is “Show, don’t tell.” As readers and audience members, we want to put clues together. We don’t need you as the writer to put them together for us. Showing character traits as opposed to naming them goes a long way to create intrigue. Take this example from “Battle of the Bastards,” episode 6-9, written by David Benioff & D.B Weiss.

Daenerys’s lack of reaction to bombs going off is very interesting, especially as it’s contrasted with Tyrion’s very natural human reaction. If you can make your audience think, “What’s up with Dany?” we’ll stick around for the rest of the story. Maybe I’m projecting, but I think it forces us to actively wonder: Could her lack of an emotional response be a symptom of psychopathy?

We also don’t even really think about it because the opposites dynamic between the two characters is so much fun to read/watch.

BACKSTORIES

After presenting Daenerys’s behavior, I would be remiss not to talk about the importance of backstory. Game of Thrones is the ideal study script if you’re looking for ways in which writers subtly plant clues that get you more interested in where the story is going. Recall this exchange of dialogue in which Cersei and Tyrion discuss whether or not Joffrey’s sadistic behavior might be due to his being born of incest. (“A Man Without Honor,” episode 2-7, written by David Benioff & D.B. Weiss)

Your mind instantly goes to the only Targaryen you know (Daenerys) and if she might one-day lose her mind too, but the prospect of that is heartbreaking to you because, as you see her, she’s the person who is going to save the day.

This is an example of how to most effectively reveal backstory. Backstory lands best when it changes or enriches our perception of how a character looks on the surface OR sets up a specific expectation for how we might think a character will act or be challenged in the future.

This is very different than having a character tell you about themselves; it’s not going to be mitigated by self-censorship and embarrassment. Rather, it plants future images and obstacles in your head. Images and obstacles that you know will be paid off down the road.

The entire history/mythology behind the Targaryen dynasty is the best source of backstory that George R.R. Martin and writers can possibly provide because it makes you question what will happen to a number of characters we care about in the future.

FUN, SIMPLE, PROFANE, PLAYABLE

The best writing is often the shortest and simplest.

It might surprise you to know that the scene and action descriptions for such a sprawling, fantastical, period epic are beautifully sparse and fun.

If you’re looking for scripts with description that is minimal and easy to digest and play (for the actors) as well as amusing and casual for readers, there’s a lot to be gleaned from Game of Thrones.

From “Winds of Winter,” episode 6-10, written by David Benioff & D.B. Weiss

If you can, stop in to read more. To search our library catalog, click here. As always, happy writing!