WRITING YOUR SCREENPLAY WHILE SOCIAL DISTANCING: PROSE

Should screenplays be considered literature?

The general consensus in the filmmaking community seems to be that if you want the focus to be on your words and your words alone, write a novel, a poem, a play. A screenplay is a blueprint, a game plan, a sketch to which other artists and collaborators are invited to complete the picture.

True, a script is meant to be rough, sparse and functional.

But rough, sparse and functional do not mean unimportant.

If you’re reading this, you know: The script is arguably the most critical element in making a good movie. You can’t really bake a cake without a recipe — and if it ain’t on the page, it ain’t on the… er… screen.

Screenplays ARE literature. They’re just a different kind of literature.

To write a movie is to clearly and compellingly express to a reader what they’re seeing, hearing and experiencing when they watch this movie on the screen.

Vivid, evocative language helps to create that picture and those feelings in the reader’s head. More than that, good prose makes a script enjoyable to read and can add a sense of gravitas and appeal to a project.

Writing with flair AND economy is a carefully cultivated skill. This week, we’ll look at how 10 screenplays across genres and styles pull it off. The aim is to give you tactics and inspiration in your own descriptions.

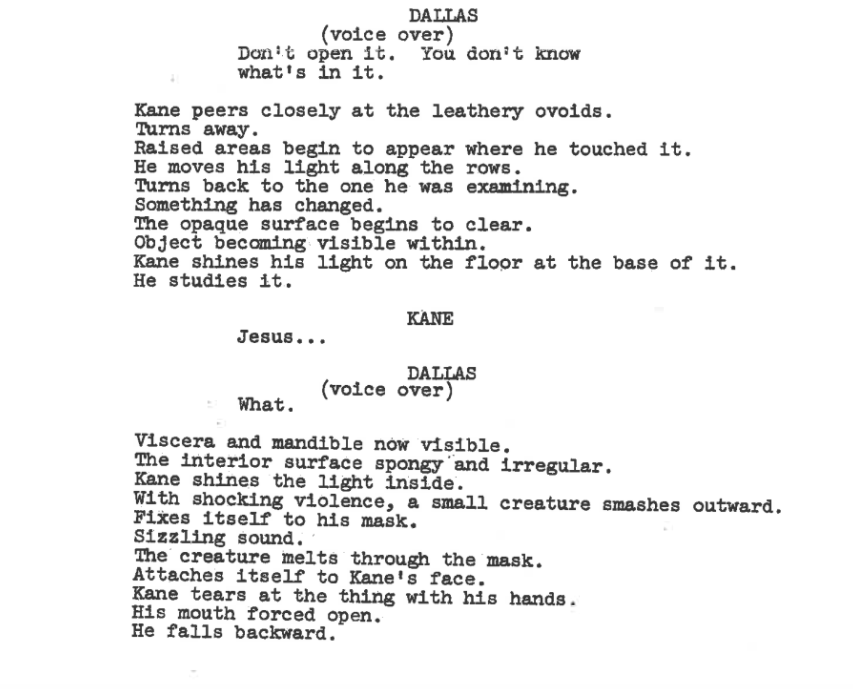

ALIEN (1979)

Screenplay by Dan O'Bannon Story by Dan O'Bannon and Ronald Shusett

The description in this script is written like a poem, which rids it of clunky nouns and articles.

Each new action or idea is presented on a new line, which keeps it moving and helps the reader see each new shot or cut.

Not only does this spare style of writing make for an effortless read, but it also suggests that the film itself will posses a clean, lyrical pace and visual style.

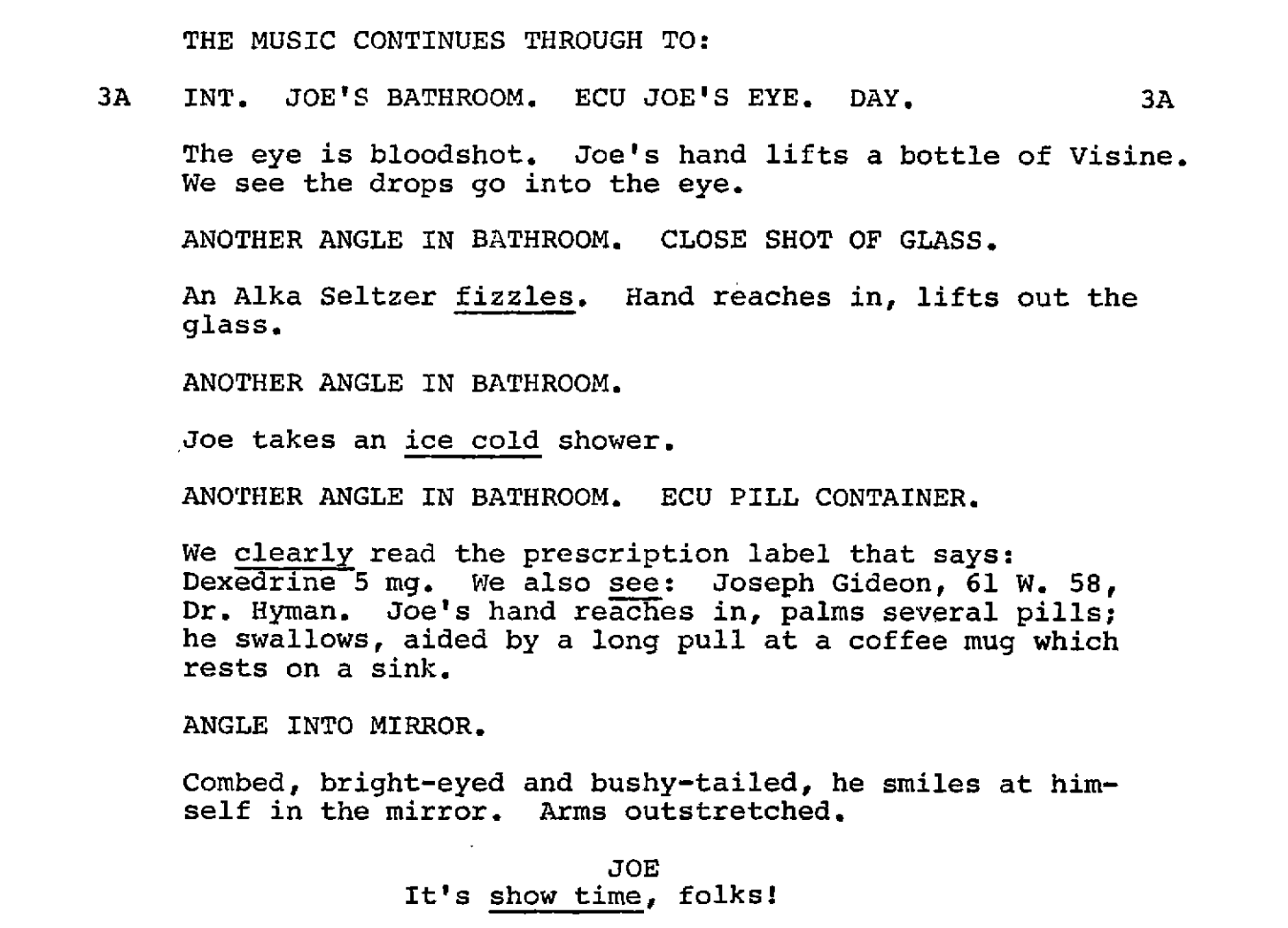

ALL THAT JAZZ (1979)

Written by Bob Fosse & Robert Alan Aurthur

Oftentimes, shooting drafts or drafts written by the director (like this one) might include specific camera directions, but this is not necessary in your early drafts.

Like the Alien script, each new sentence is a new quick action or image for the reader to focus on.

Certain words are underlined to move the reader through the paragraphs, but notice that the underlined words are arbitrary — because this sequence becomes something we see over and over again and it’s arbitrary for the character.

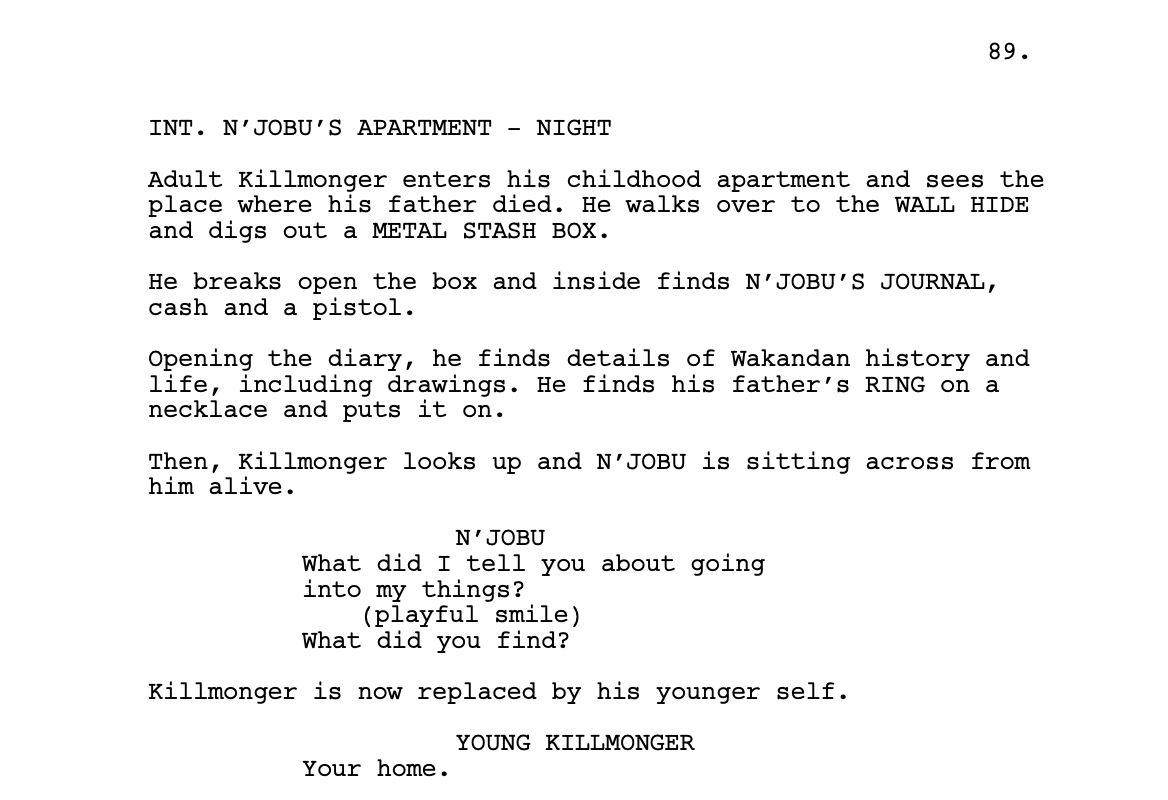

BLACK PANTHER (2018)

Written by Ryan Coogler & Joe Robert Cole

This is a helpful selection to look at as it includes ritualistic, flashback, and hallucinatory elements. Even as they deal with things that might be tough to describe, the writers keep their prose extremely direct and simple without getting bogged down in excess explanation. (Example: “N’JOBU is sitting across from him alive,” “Killmonger is replaced by his younger self,” etc.)

Note: certain props and visuals are capitalized for emphasis.

THE FAVOURITE (2018)

Written by Deborah Davis & Tony McNamara

This script proves that a film’s tone and attitude are carried in the description. Even if we never SEE the TB that the kids cough into the air, we feel it. That’s something the filmmakers and actors can play.

If the description were worded differently, this would be a different film. If you’re hoping the movie that results from your script is irreverent, it probably helps if the writing is at least a bit irreverent.

JOJO RABBIT (2019)

Screenplay by Taika Waititi

The description here is made engrossing as it’s written from the perspective of the main character. in this case, that’s a naive little Nazi boy, Jojo.

Rather than seeing A GIRL at first, Jojo sees A SKINNY PALE CREATURE, which piques our curiosity as readers. The point is that the description isn’t omniscient. We’re learning and feeling (including fear and intrigue) with the character.

Like Black Panther, significant images and actions are capitalized for emphasis. Also, notice how Waititi leaves visual breadcrumbs to create a suspenseful sequence, i.e. - “a candle, bedding, a plate, a fork…”

JURASSIC PARK (1993)

Screenplay by Michael Crichton and David Koepp

Based on the novel by Michael Crichton

Here, the writers rid themselves of extra nouns and articles with commas and dashes.

The tension ramps up around several instances of “BOOM. BOOM. BOOM.” “BOOM” is an onomatopoeia that invokes a feeling of doom.

Scripts (and especially resultant movies) become engaging when the writer leaves visual clues rather than spelling things out overtly. The vibrating glasses, the dangling security pass, the missing goat, the disembodied leg… As our brains try to piece together the sequence of what we’re witnessing, our heart rate goes up. With each new clue and revelation, we wait for something scary to pop out at us.

LEGALLY BLONDE (2001)

Screenplay by Karen McCullah Lutz & Kirsten Smith

Based on the book by Amanda Brown

The writers here use funny verbs and nouns. “Tush out, knee cocked” is much funnier and simpler than say, “She sticks out her butt and bends her knee.” There’s rhythm to it, which is all-important, especially when writing a comedy.

LOST IN TRANSLATION (2003)

Written by Sofia Coppola

How do you make riding around on a subway and walking around Tokyo in an aimless daze something that grips the reader on the page? The answer is in the flashes of detail.

When we can see the details in something — as in a close-up — we know it’s important. Lost in Translation is about the sensory experience and the details of a particular place. The description reflects that. Coppola conveys these details clearly, but quickly, e.g. blots his face, erotic comic, businessman in a suit playing Dance Dance Revolution.

This script shows that you can immerse a reader in specificities without becoming wordy.

THE TERMINATOR (1984)

Written by James Cameron & Gale Anne Hurd

It’s been said that James Cameron doesn’t write words, he paints pictures. Much of this has to do with his vivid word choices and active verbs, which are so essential, especially when writing an action movie. Think: jerks, brandishes, bursts.

YOU’VE GOT MAIL (1999)

Screenplay by Nora & Delia Ephron

Based on the play Parfumerie by Nikolaus Laszlo

We’re including this because it’s fun and useful to see how Nora and Delia Ephron describe what we see on a computer screen, especially in the days when e-mail was a new and burgeoning presence in our lives…

If you have questions about these or other scripts, as always send us an e-mail at library@wgfoundation.org.

Until next time, happy writing!