WRITING YOUR SCREENPLAY WHILE SOCIAL DISTANCING: SUBTEXT

It’s a basic, universal survival instinct:

Look strong and stable.

Why? Because the weak, slow and inadequate ones get lost from the herd and devoured.

Human beings operate from a place of self-protection. We find it in the way that we speak to and treat one another. The words we say are the armor we use to keep ourselves from exposing our sad truths.

Seeing the truth underneath what a person says is the joy of engaging with a movie or TV show. Finding and bringing to light the essential core that exists underneath all the bullshit in the world is the very purpose of art.

In dramatic writing, we call this subtext.

Subtext is a hard thing to explain or teach because it’s about feeling beyond the words a person says. It’s about seeing the self-protection. It’s about intuiting the whole iceberg from just a glimpse of the tip that rests above water. This is both a writing and life skill that requires careful cultivation.

Just like when you write a poem every day, you train yourself to see the poetic and the beautiful in the smallest, most mundane of things… if you regularly look beneath what’s being said, you’ll see the essential, subliminal truths that exist everywhere.

Watch the news. You’re sure to see someone saying they’re in great health even as their bodily agony belies their words. A morose person will usually say they’re happy. An upset person will work extra hard to convince you they’re fine. A greedy person will try their darnedest to make you believe they’re charitable or generous.

Everybody tries look faultless to protect themselves, but as a writer, your job is to help us see the vulnerability and to the find the truth.

Over the past two weeks we’ve addressed character voice and dialogue. This week we’ll look at subtext because it’s an essential component of communicating via characters and story. One way to get better at harnessing subtext in your own writing is to seek it out in the scripts you read. With this in mind, we’ll offer examples from an array of different films, identifying the techniques used by the writers.

BEACHES (1988)

Screenplay by Mary Agnes Donoghue

Based on the novel by Iris Rainer Dart

How boring, flat and uncomfortable would this scene be if CC simply said to her best friend Hillary: “I love you, but I always thought I hated you, so I never showed it. You don’t know how much I really care!”? It’s much easier to speak about a dog than to speak directly to a friend about FEELINGS.

This is what we might call thematic subtext. It explores the themes of the movie: Friendship and loss while also foreshadowing what CC is going to go through later in the story, losing Hillary. One might argue that the whole exercise of watching a film is to LOOK for a theme. If a writer expresses the theme outright, they rob their readers of searching for it.

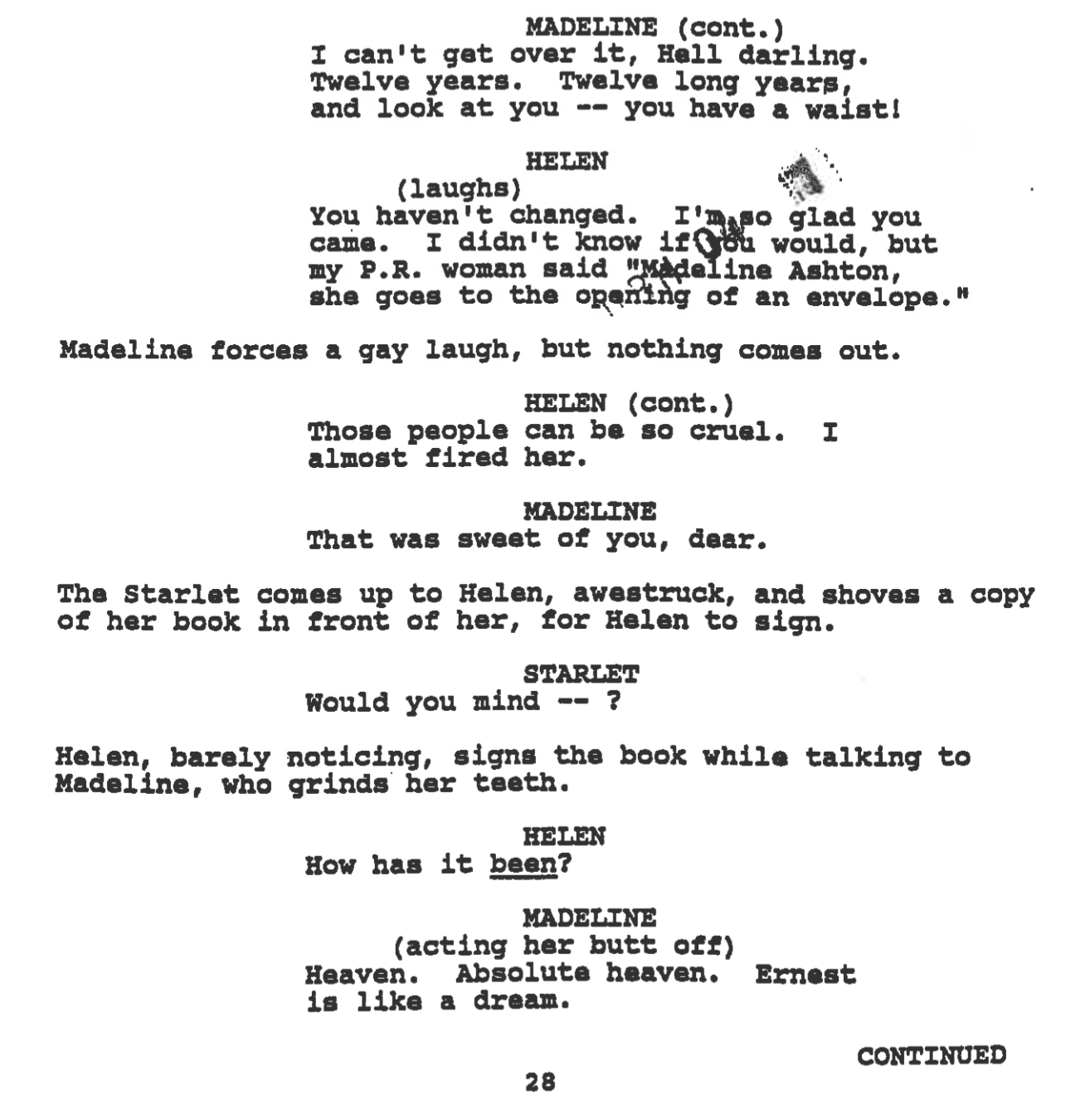

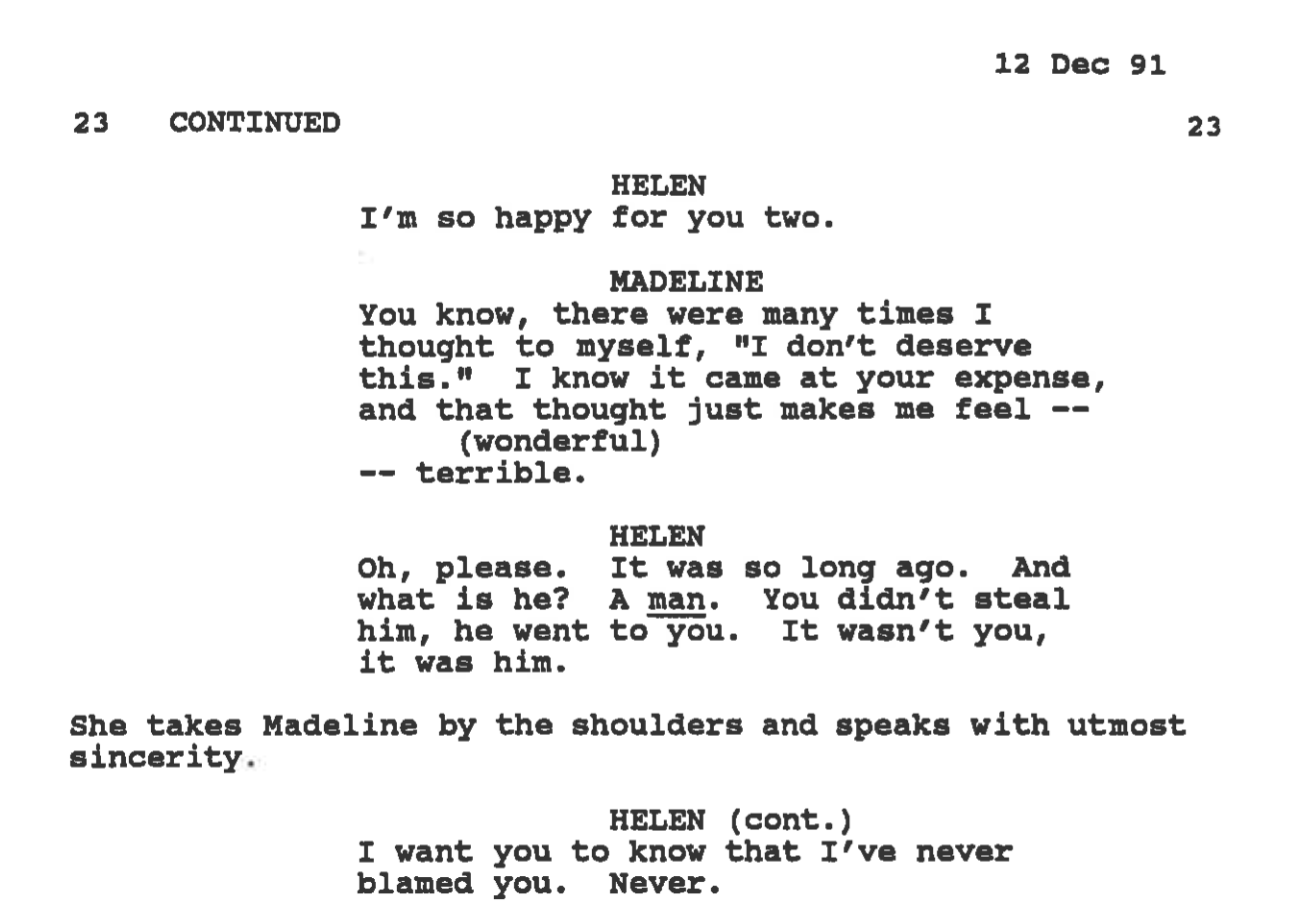

DEATH BECOMES HER (1992)

Written by Martin Donovan & David Koepp

Let’s call this ironic subtext, where every word out of Madeline and Helen’s mouths is the exact opposite of what they really mean.

We have all been in a position where we loooooathe somebody, but have to act in a civilized manner; where we want to kick somebody, but are forced to kiss them; where our polite decorum seethes with bitterness or jealousy.

Think — a boss you despise asks you to stay late on a Friday night for an assignment you think is totally pointless. You might retort, “Sure! No problem,” but is that really what you MEAN when you say it?

DOUBLE INDEMNITY (1944)

Screenplay by Billy Wilder and Raymond Chandler

Based on the novel by James M. Cain

This is one of the most oft-cited examples of subtext in a movie, but we’ll repeat it now because it’s a great example of role-playing subtext.

Sometimes when a topic of conversation gets a little too salacious or uncomfortable, a character might take the heat off themselves by playing a role or pretending to be someone else.

When Phyllis realizes that Neff is coming onto her, she polices him, but he plays right along. If they’re not themselves, they don’t have to take responsibility for their emotions or for the wrong turn they’re taking.

THE HURT LOCKER (2009)

Written by Mark Boal

We felt it might be helpful to include this as a reminder that not all subtext is related to dialogue. Sometimes subtext can be visual subtext.

With the context of having seen James diffusing bombs in incredibly high pressure situations, we get exactly how incongruous he feels in a grocery store aisle, when faced with a mundane task like selecting a cereal. That’s what’s going on underneath what we see.

LOVE JONES (1997)

Written by Theodore Witcher

Subtext can be a staple in the romance genre. In this final moment of Love Jones, Nina mitigates the tension of reuniting with Darius by referring to him in the third person, like she’s talking about somebody who ISN’T him. Can you imagine if she said, “I had a jones for you. I think I left you hanging,” or if he said, “Am I fine?”

We’ll call it third person subtext. Characters might do this if directly referring to themselves or each other is too awkward, painful, embarrassing, etc. Sometimes they’ll tell a story about someone else, but we know they’re really talking about themselves.

ONE FLEW OVER THE CUCKOO’S NEST (1975)

Screenplay by Lawrence Hauben and Bo Goldman

Based on the novel by Ken Kesey

In real life, people don’t often say, “I’m right. You’re wrong,” or, “I have the power here and you have to do what I say.” Rather, people jockey for control or authority in arguing over small, seemingly banal things.

This conversation between McMurphy and Big Nurse Ratched is not AT ALL about music or pills. Rather, it’s about who is in charge of the hospital — the patients or the administration? In this scene, despite McMurphy’s best efforts, the nurses maintain the upper-hand, even using subtle humiliation to get him to back down.

If you need a name for this kind of subtext, maybe it’s superiority subtext.

SIDEWAYS (2004)

Screenplay by Alexander Payne & Jim Taylor

Based on the novel by Rex Pickett

Let’s call this an example of metaphoric subtext. It’s very similar to the third-person subtext used in Love Jones, but this is even more blatant. This is also a much-noted example of subtext, but it’s worth presenting again as its overtness makes it a great teaching scene.

In the scene, two wine enthusiasts talk about their passion for the beverage, but the wine becomes a conduit through which they actually talk about themselves.

As we’ve repeated throughout this post, it’s easier to talk about dogs, speeding tickets, other people, music, wine, ANYTHING than it is to talk about or really deal with ourselves. Most great scripts are completely laden with subtext. Hopefully these examples help you to refine your ability to intuit it.

For additional questions about these and other scripts, as always, e-mail library@wgfoundation.org

Until next time, happy writing!