TV FORMAT FUNDAMENTALS: ANIMATED SITCOMS

Here in the WGF Library, our aim is to help you hone your ability to study TV shows (and their scripts). After all, it’s through this rigorous study that one hopefully becomes a better, more thoughtful writer. With this in mind, we jump back into TV Format Fundamentals, a blog series that explores the background, elements and style of a handful of scripted TV formats.

This week we're looking at animated sitcoms.

As we’ve explored in previous installments of this series, sitcom stands for “situation comedy.” In our post about multi-cam sitcoms, we defined situation comedy as “shows in which a specific group of characters find themselves in a new, ridiculous situation with each episode. The humor occurs as the characters struggle to get out of that situation.”

To peer closely at the DNA of the animated sitcom, we must go all the way back to the origin of the live-action sitcom. Families—biological families, chosen families, workplace families, school families—are the most fertile ground for situation comedy because you have a group of characters that are naturally always together to get into “situations.”

In developing their seminal animated Stone Age series THE FLINTSTONES (the first animated sitcom to air in primetime, CBS 1960) producers William Hanna and Joseph Barbera took great inspiration from THE HONEYMOONERS (which aired a few years prior).

On Wikipedia, THE HONEYMOONERS is described as such: “[the show] follows New York City bus driver Ralph Cramden, his wife Alice, Ralph’s best friend Ed Norton and Ed’s wife Trixie as they get involved in various schemes in their day-to-day living.” You don’t have to look too hard to see how THE FLINTSTONES follows this template almost exactly. Its logline could be: the show follows Stone Age construction worker Fred Flintstone, his wife Wilma, Fred’s best friend Barney Rubble and Barney’s wife Betty as they get involved in various schemes in their pre-historic day-to-day living.

THE JETSONS, the futuristic counterpart to THE FLINTSTONES, which premiered in 1962 (also on CBS), seems to draw on FATHER KNOWS BEST (1954-1960) for inspiration. Both shows feature a hapless father, his spendthrift wife, a hip/boy-crazy teenage daughter (or two) and a genius young son. Note that while the show may take place far into the future with flying cars and robot housekeepers, its characters reflect staunchly 1950s stereotypes.

We mention all of this to illustrate how animated sitcoms are firmly entrenched in the conventions of their live-action counterparts. The difference is just animation.

So, what does this mean for the way animated sitcom scripts are structured and formatted?

Both THE FLINTSTONES and THE JETSONS predate formal act structure in their scripts, but if you watch the shows on HBOMax and pay attention to the commercial blackouts, you'll notice a distinct three-act episodic structure. Before the first commercial, the problem of the episode is introduced, i.e. Fred, Wilma and the Rubbles get invited to a fancy gala, but fret because they're not fancy enough for said gala. Between the first and second commercial, complications ensue as the characters prep for attending the gala, then after the second commercial, they actually go to the gala.

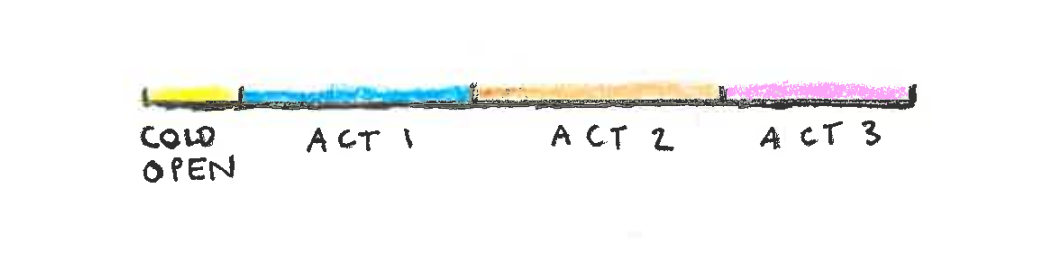

Sometimes episodes begin with a short cold open that previews what the episode will be about… but each episode contains three distinct acts — a beginning, a middle and an end — much like a feature screenplay.

Over the years, the act structure for animated sitcoms hasn’t changed much. THE SIMPSONS, FUTURAMA, FAMILY GUY, AMERICAN DAD and KING OF THE HILL all use three simple, straightforward acts.

Some animated sitcoms utilize a four-act structure. Examples include BOB’S BURGERS and THE GREAT NORTH. The first act is the setup, acts two and three feature complications and higher stakes, then act four wraps everything up:

In prepping for this post we found one animated sitcom that uses two-act structure. That show is CENTRAL PARK. The easiest way to understand two-act structure is that the characters get into trouble in the first act and struggle to get out of it in the second:

A lot of cable and streaming animated sitcoms use the classic three-act structure, but add a cold open in most episodes. Examples of this type of structure include BOJACK HORSEMAN, ARCHER and HARLEY QUINN.

Finally, you might look at the scripts for a streaming show like BIG MOUTH and see no act breaks nor a cold opening. As we’ve discussed in previous posts in this series… just because act breaks are not specified in the scripts pages does not mean the writers are not thinking about act breaks.

Most animated sitcom scripts are formatted with double-spaced dialogue, much like multi-cam sitcom scripts. Then, the description is single spaced. Oftentimes, scene headings and sound effects are bolded. This is generally the case with animated series, but should not be taken as sacrosanct. Some shows — like BOJACK HORSEMAN — single space their dialogue and IT’S OKAY.

In live-action sitcoms, emphasis is usually on the timing or physical comic abilities of the actors. Animated sitcoms work best when the creators take full advantage of the animation. If the main character isn’t an anthropomorphic horse, if Homer’s wife doesn’t have three-foot high blue hair, if the Flintstones have a dog as a pet rather than a dinosaur, why would you make the series animated? Great animated shows take full advantage of animation where you can present out-of-this-world scenarios and jokes. Something to consider when you’re developing an animated show.

CASE STUDY:

FUTURAMA “Pilot”

Written by David X. Cohen and Matt Groening

If sitcoms are foremost about a family or group that can run into countless funny “situations,” a great sitcom pilot is about meeting our primary group of characters and setting up the world or overarching “situation” they’re in. A pilot script that does this particularly well is FUTURAMA (1999), which is why we’ve chosen it as our case study this week. In addition to introducing its central gang of misfits with pathos and wit, the pilot does a great job establishing the three-act structure it will use in subsequent episodes.

FUTURAMA is about a good-natured slouch named Fry, who works delivering cargo planet-to-planet nearly 1000 years in the future. His crewmates include Leela, a cycloptic alien (or so she believes herself to be at first) and Bender, a foul-tempered robot who drinks heavily. The pilot is where we meet them and the far future that they inhabit.

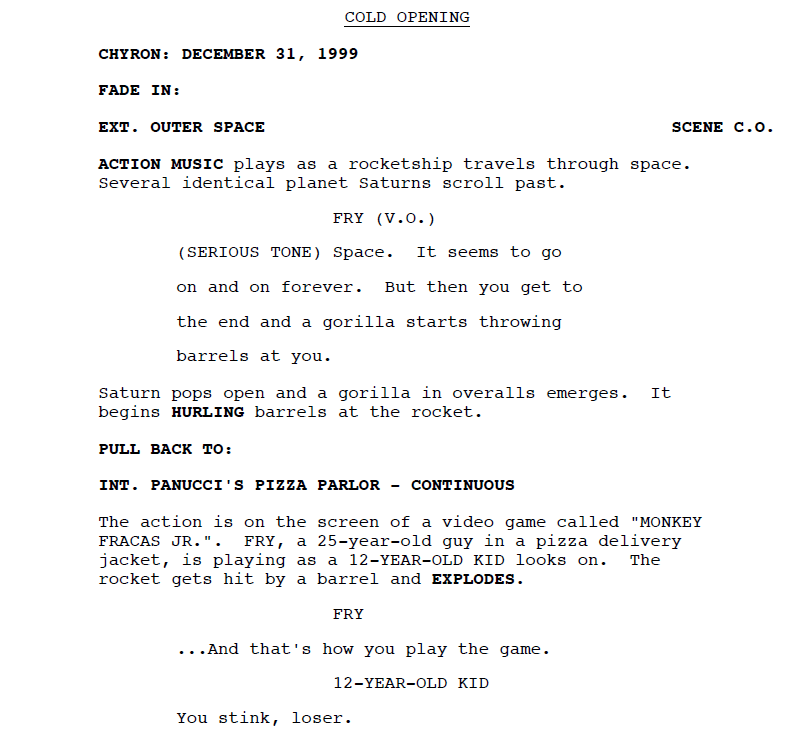

COLD OPENING

While many other FUTURAMA episodes don’t include it, the pilot features a brief cold open. It’s where we meet Fry, a New York City pizza delivery boy who (it appears) would rather be playing video games than delivering pies. He lives in the year 1999. On the first page, we see him get made fun of by a kid. Ouch! This starts to pique our empathy.

Over the course of the cold open, we watch Fry on New Year’s Eve get dumped by his girlfriend and delivery a pizza to a cryogenic laboratory where he calls out that he has a delivery for “I.C. Weiner.” Aww poor guy. He walked right into it. He also trips right into a cryogenic tube as New York City counts down to the new millennium.

And, like Dorothy emerging from her tornado-spun Kansas house into the world of Oz, Fry emerges from his cryogenic slumber into a New York City 1000 years in the future. End of Cold Opening.

ACT ONE

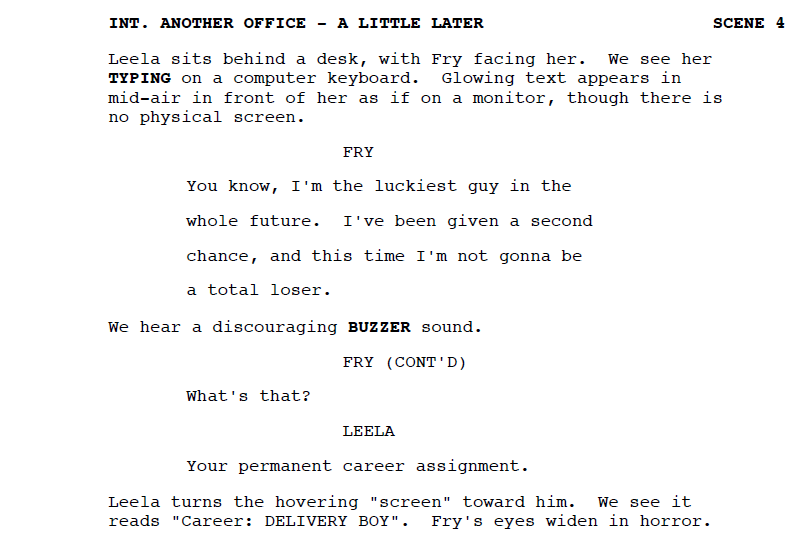

After the cold opening, the first act begins on page 7 as Fry begins to figure out where he is and what’s happened to him. The year is 2999 and Fry believes he’s been given a fresh start. By the way, characters seeking a fresh start are a fantastic way to open a television series because it means right from the get-go the character is in pursuit of something.

Fry’s hopes for a new start 1000 years into the future are dashed when he meets Leela, a one-eyed alien, whose job it is to “chip” him with his permanent career assignment, which is – much to his horror – delivery guy… even 1000 years into the future. Fry also finds out from Leela that he has a great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great nephew, a haggard old man by the name of Professor Hubert J. Farnsworth.

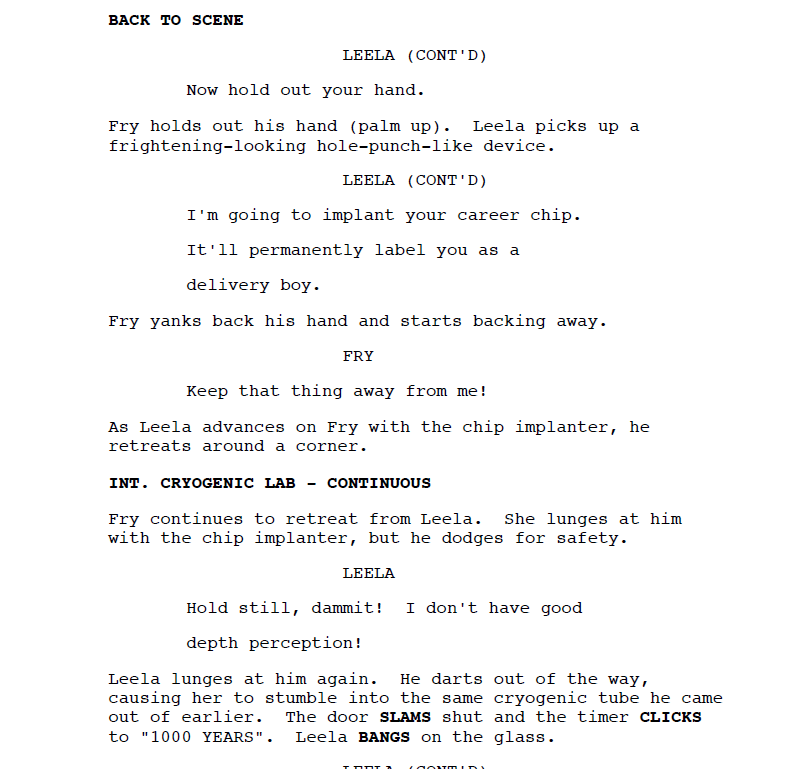

Fry manages to evade Leela and her chip implanter for the time being. As you can see, Leela also lands in a cryogenic tube. However, Fry has mercy on her and sets the timer for 5 minutes. It’s a favor he does for her that will later be paid off.

On escaping Leela, Fry goes in search of his nephew, Farnsworth. He finds what looks like a phone booth, but it’s really a “suicide booth.” He ends up stepping inside the suicide booth with one very unhappy robot named Bender. We break for commercial wondering if Fry will survive this horrific ordeal, then onto…

ACT TWO

Act two begins on page 20. Spoiler alert: the suicide booth proves ineffective. The act begins with Fry and the robot, Bender, unscathed. Now what are they gonna do?

Meanwhile, Leela has to report that Fry got away from her. Her boss insists that she track him down and implant him with that chip. After all, it’s her job.

As Leela gets harangued by her boss, Fry and Bender go for a drink and get to know one-another. Think again of THE WIZARD OF OZ… Dorothy meets the Scarecrow, then she meets the Tin Man. Fry learns that Bender is a robot who is very dejected with his lot in life.

Given that he is unhappy himself with the prospect of being a lifelong pizza deliverer, Fry empathizes with Bender and the two become friends.

Their bonding is interrupted when Leela shows up at the bar in pursuit of Fry! As Fry and Bender see her and run away, Leela calls for back-up! The two hide in a museum, specifically in the “20th Century Gallery.” The show’s creators obviously have great fun with the museum, making it a testament to “the past” which is really our present (or it was our present in 1999).

Leela’s back-up comes in the form of two police officers, Url and Smitty. They all reach the 20th Century Gallery just as Fry and Bender are being attacked by the heads of former U.S. Presidents.

Url and Smitty draw what look like light sabers and plan to brutally attack Fry and Bender.

Leela presumably feels bad for Fry and Bender and tries to get the officers to back off, but they make fun of her (which makes us feel for her). She kicks and punches enough at the officers that Fry and Bender are able to make an escape.

They then find themselves in a back room of the museum where the only escape is a small window with bars on it. Bender doesn’t believe he can destroy the bars. While he’s a “bender” it’s just not what he’s programmed for.

Act two ends with Bender summoning his courage and ripping out the bars, but subsequently destroying his arms in the process. Note that act breaks or commercial blackouts almost always end on a question… Will they successfully escape? End of act two.

ACT THREE

Act three begins on page 32. Having escaped, Bender and Fry walk around the ruins of old New York City. This makes Fry sad. What he’s lost in traveling so far into the future starts to weigh on him.

At this moment that Leela catches up with them, chip implanter in hand. Fry just wants to be left alone… but it seems Leela understands Fry more than either of them realizes.

Rather than implant Fry with the career chip, Leela decides to quit HER job. This leaves our new trio directionless and without a clear plan. It’s here that Fry remembers his great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great nephew Farnsworth… and it’s off to see the Wizard… er… the Professor!

It’s New Year’s Eve again… 2999.

Fry finds his Uncle and introduces himself.

Professor Farnsworth has a spaceship but lacks a crew to fly it. As it turns out, Leela knows how to fly a ship. Leela, Fry and Bender agree to be Farnsworth’s crew… but what exactly will they be doing out there in space?

At the end of the episode, Fry is essentially back where he started, a delivery boy with a newfound crew and family. Pilot episodes are critical for getting an audience on board with the show's central characters. Here, we empathize with Fry, Leela and Bender as they are all misfits or misanthropes wanting a little something more from their existence. Who can't relate to that? We want to follow them through all their foibles and hijinks. The pilot also facilitates a perfect setup for new situations to arise with each new episode AND establishes the three-act structure through which those stories will be told. The script ends on page 46 (but keep in mind that the dialogue is double-spaced).

If you want to talk more about animated sitcoms, make an appointment to visit the WGF Library or e-mail us at library@wgfoundation.org. Until next time, happy writing!