The Screen Writers’ Guild: An Early History of the Writers Guild of America

By Hilary Swett, Archivist, Writers Guild Foundation, 2020

Since the earliest days of the movie industry, screenwriters have been educating, organizing, gathering, and celebrating one another in an effort to enhance the quality of motion pictures, elevate the craft of screenwriting, improve relations with producers, and gain better working conditions. The Screen Writers’ Guild, the precursor to today’s Writers Guild of America, officially organized as a labor union on April 6, 1933. The next ten years of the SWG were dramatic and challenging, and are well chronicled in books and interviews which examine the founders and organizing principles (referenced at the bottom of this page).

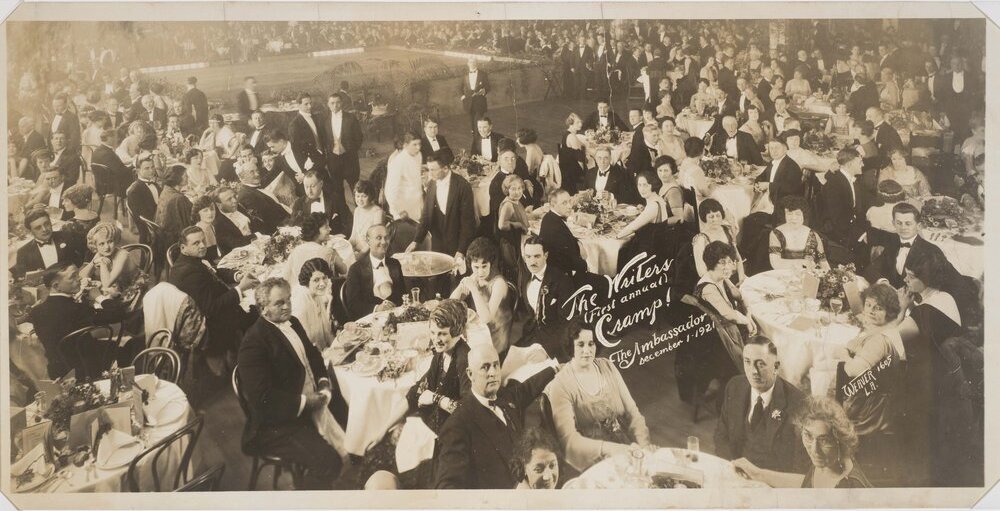

The Writers First Annual Cramp on December 1, 1921. Held at the newly opened Ambassador Hotel, located in what is now Koreatown. Photographed by Los Angeles banquet and panoramic photographer Miles Weaver. Digital copy in the Mary H. O’Connor Collection. Scanned from the original held by the Harry Ransom Center.

The Guild’s 1933 founding is often contextualized in terms of larger American narratives such as New Deal legislation, which led to a wave of unionization across the United States, and screenwriting’s relationship to copyright, authorship and ownership. Historians have also examined the politics of Guild founders such as John Howard Lawson that have a direct link to the Hollywood Blacklist and writers testifying at the HUAC hearings of 1947 and 1951.

But ideas about writers working collectively toward a better future have roots that date back to the earliest days of the movie industry. Film writers, who had been gathering to talk about their profession as early as 1913, worked together to form the Screen Writers' Guild in 1920 as a social and professional organization. Its activities and goals during the 1920s laid the groundwork of foundational principles under which the SWG reorganized officially as a union in 1933 and which the WGA still follows today.

The Writers Guild Foundation Archive is full of unique treasures and tales from the trenches of screenwriting. We collect scripts and related material from writers and we preserve records dating back to the Guild’s inception as a labor union in 1933. Descriptions of some holdings are available at the Online Archive of California. We are fortunate to have the collection of an early scenario writer, Mary Hamilton O’Connor, that reveals some activities of the Screen Writers’ Guild and predates the founding of the union by more than a decade. Work from this time period is not well documented, but the O’Connor Collection shows scenario writers engaged in the critical work of network-building and professionalization during the silent era. Research reveals that while the Screen Writers’ Guild of 1920 looked different from its 1933 manifestation, its work was instrumental to its foundation and success.

Prehistory

In the beginning, screen stories were simple. Scenario writers were considered a small part of the moviemaking machinery and would go uncredited. Dialogue title cards were introduced in the mid-1910s and suddenly actors were “speaking” and showing character. As the fledgling movie industry grew alongside ticket sales, so did the ambitions of producers and directors to make more and longer movies. Managing multiple productions and changing audience tastes necessitated personnel dedicated to the crafting and managing of stories. Studios created scenario departments. Cinematic storytelling became more codified in form and purpose.

Board members of the Photoplay Authors’ League, including Mary H. O’Connor, D.W. Griffith, and Frank E. Woods. From The Moving Picture World, July 10, 1915.

As the young industry evolved during the 1910s, writers and story editors identified a need and desire for professional camaraderie and a way to protect their interests. The Authors’ League of America (now the Authors Guild) was formed in New York in 1912 to represent many of the nation's writers, including dramatists, but the League and literary culture were not necessarily a good fit for writers in the movie industry. Ownership and authorship were fundamentally different from that of novelists and playwrights, even at this early stage, and screenwriters did not own copyright on their work. So this period saw the creation of several clubs specifically for film writers. One of the first, the Inquest Club, was founded in 1913 in New York by film critic, journalist and scenario writer Epes Winthrop Sargent. The Ed-Au (Editors-Authors) Club, later renamed Photodramatists Inc., was also founded in 1913 and was more exclusive, requiring six produced scripts for eligibility. These clubs would hold dinners, invite speakers and served as forums to share successes and vent grievances.

One of the most significant antecedents to the Screen Writers’ Guild was the Photoplay Authors’ League, established in 1914 in Los Angeles. This club was founded as the industry was expanding its reach to the West Coast, which would eventually become the center for film production. The Photoplay Authors' League (PAL) required ten produced photoplays to become a member, which points to the growing professionalization of the craft. It was founded by notables such as Lois Weber, Hettie Gray Baker, Marc Edmund Jones and Richard Willis. Frank E. Woods, then head of Mutual’s scenario department, was the organization's president. He would later be a founding member of both the SWG in 1920 and the Academy in 1927. PAL's goals focused on enhancing recognition for photoplays and photoplay authors, improving photoplay quality, and providing copyright protection. It launched a campaign against the many screenwriting schools which had cropped up, promising wealth and success to aspiring writers but delivering neither. PAL even published a magazine called The Script. The organization existed for only two years but planted the seeds of a screenwriters’ community and shared professional goals. During this time, many scenario writers were also members of the Authors' League, which in 1919 had established a Dramatists branch, but writers in Hollywood still saw a need to form an organization of their own, made up only of film scenario writers and based where they worked and lived.

Founding and Early Work

The Screen Writers’ Guild was formed in the summer of 1920 by many of the same key players who had been involved in the earlier clubs. Thompson Buchanan and Rupert Hughes, New York dramatists who had transitioned successfully to working as film writers in Los Angeles, were instrumental in the establishment of the SWG. They were also both on the Executive Council of the Authors’ League. Hughes had helped found ALA and served as President. They realized that film writers could be well served by joining with the established Authors’ League and quickly garnered support among the movie community.

On June 24, 1920, twelve writers met at the home of Thompson Buchanan and formed the “Temporary Executive Committee” of a new organization, to be called the Screen Writers’ Guild and organized as a branch of the Authors' League. The group was formed as a “fraternity to protect and promote the interests of its members.” They held a recruitment dinner on July 8 at the Los Angeles Athletic Club, chaired by Frank E. Woods, where over one hundred writers attended to discuss the purpose of the group. On July 9th, the SWG ran an open letter in Variety inviting all industry writers to apply for membership. In the letter, the SWG explained in broad but dramatic language that the purpose of the organization was to “correct the numerous abuses to which the screen writer is subject” and to establish him in “the position to which the importance of his work entitles him.” The letter outlined their six objectives, which included establishing a registration system, obtaining fair screen and advertising credits for writers, and adequate compensation and royalties.

Mary H. O’Connor at Paramount. 1921. From Wikimedia Commons. Accessed 11 Nov. 2020.

The stated principles demonstrate a growing assertive stance regarding the importance of the writer and the need for the writer-producer relationship to be articulated and maintained. These goals, reflective of ALA’s goals, set the writers on a path to professionalization and are still at the core of the Writers Guild's mission today. From these early days, writers knew that credit and authorship would be the most important elements of their professional success.

On July 16th, Thompson Buchanan was elected President, with Mary H. O’Connor as Vice President. O’Connor had been an organizer of the Photoplay Authors’ League, along with Frank Woods, D.W. Griffith and others. Mary H. O’Connor was a magazine and newspaper writer who found great success as a scenario writer, editor and story department manager between 1913 and 1926. She worked at a number of film companies, including under D.W. Griffith, and worked for a number of years under Frank Woods at Lasky. Woods was named as chairman of the committee to establish a constitution and by-laws.

On Aug 28, 1920 the SWG held its first social event, a barbecue at Brunton Studios (which would later be part of the Paramount lot). Rupert Hughes was the guest of honor and spoke of the operations of the new group. The leaders quickly got to work and on October 21, 1920, the Authors’ League had officially incorporated the new branch of screenwriters and the Screen Writers’ Guild of the Authors’ League of America was born.

In January 1921, the group published its constitution and put forth its principles, which differed slightly from the Variety statement and included fighting censorship laws in its agenda:

To secure copyright protection for original story manuscripts and scenarios of motion pictures;

To free American motion pictures from censorship;

To insist on more cooperation between the producers of motion pictures and the Guild's members;

To procure adequate screen, advertising, and publicity credit;

To help its members secure adequate compensation and recognition for their efforts.

Qualifications for membership in the SWG were broadly inclusive. Any person who derived income from writing for the screen, or who had one produced original story or continuity, could join. Dues were set at $60 per year (roughly $800 in today’s terms) and included membership in the Authors' League of America as well. Applicants also had to be nominated by two existing members and approved by the board.

By February 1921, the group rented a temporary office in the Markham Building at 6372 Hollywood Boulevard, which was also home to the American Society of Cinematographers (founded in 1919) and production companies and other Hollywood firms. In July 1921, Frank Woods was elected President of the SWG with June Mathis as Vice President. The Guild moved toward its goals rapidly in the first few years, making progress that propelled the profession forward and setting precedents that can be seen in the work of the WGA today. They worked toward a basic contract, proper credits and arbitration control, and to improve the image and professionalization of the field. This took several forms:

The July 1921 issue of The Photodramatist, published by the Palmer Photoplay Corporation, was the inaugural issue as the “official organ” of the Screen Writers’ Guild.

A grievance committee arbitrated matters of credit and payment if producers and writers could not come to agreements on their own. As it remains today, this process was confidential so all parties could avoid embarrassment.

A legal committee sought to establish a standard contract similar to contracts adopted by the Dramatists Guild in 1920 and 1926. (Efforts throughout the 1920s and 1930s were unsuccessful and writers would not have a Minimum Basic Agreement with producers until 1941, signed in 1942.)

A manuscript registration service started in 1922, similar to what is still in place today, with the aim similar to copyright protection,.

An existing magazine, The Photodramatist, became the “official organ of the Screen Writers’ Guild” with the July 1921 issue. From 1921-1923, the publication contained updates about the work of the guild and members.

In efforts to fight censorship. Frank Woods was named the first chairman of Affiliated Picture Interests, an effort of fourteen industry branches that came together in March 1921 to fight legislation that the film industry feared would adversely affect business. For example, they worked in states that passed “blue laws" which prohibited movie theaters from opening on Sundays.

During these years, the SWG also worked to raise the profile of the screenwriting profession. For instance, the 1920-21 edition of the Wid’s Yearbook lists the Screen Writers’ Guild board information as well as an index of writers’ credits. The previous year, writers were not even included in this directory, which was an encyclopedic reference book for the movie industry. Guild leaders also joined together to polish the Hollywood image. The SWG generated publicity in the trades to offset the scandalous news stories of the Fatty Arbuckle rape scandal in 1921 and the murder of William Desmond Taylor in 1922. The SWG also took up investigation into the myriad screenwriting schools that had appeared on the scene, and tried to educate the public about the art form to limit misinformation from disreputable sources.

The Writers’ Club

When the SWG was formed in 1920, writers made it clear that they not only wanted to improve their professional prospects but also wanted a place of their own to socialize and network. In addition to being the first elected Vice President of the SWG, Mary O’Connor was an organizer of the social arm of the Guild called The Writers’ Club. She was the majority shareholder in a company called The Las Palmas and Sunset Corporation, the company under which the SWG transacted business. One of the first activities of this company was the purchase of a mansion at 6716 Sunset Boulevard, which was then converted into a clubhouse. (By 1923, the address of the building became 6700 Sunset Blvd.) This clubhouse would serve as a gathering place and SWG headquarters until 1933, when the newly revitalized union moved to 1655 N. Cherokee.

The Writers’ Club, on Sunset Blvd. was transformed from a mansion into a gathering place suitable for the Hollywood literati, with a dining room, billiards room, and other amenities typical of social clubs of the time. Most importantly, it had a small theater where many one-act plays were staged by the writers, actors and directors who were club members. From the Security Pacific National Bank Collection/Los Angeles Public Library.

The clubhouse was outfitted with a dining room, pool tables and a other amenities and christened with a Halloween party on October 29, 1921. Membership was open to anyone working in the Hollywood community. On December 21, 1921, The Writers held a ball at the Ambassador Hotel, which was called the First Annual Writers Cramp. It attracted more than a thousand partygoers and generated $6,500 in profit. It was a hot ticket, according to the gossip columns of the day. In 1922, a small theater was built on an adjacent lot. In October 1923, the Writers and SWG officially split into two bodies, each with their own board and officers. From that point on, the Screen Writers' Guild was open only to scenario writers, while The Writers’ Club membership opened up to the Hollywood community at large.

Over the years, club members put on numerous one-act plays, dinners and other social events which brought together writers, directors and actors to celebrate talent and facilitate networking. In 1930, Samuel French published Hollywood Plays: Twelve One-act Plays from the Repertory of the Writers' Club of Hollywood. The Writers’ Club continued staging plays until the mid-1930s.

Board members of the club included Mary O’Connor, Frank Woods, Thompson Buchanan, June Mathis, Marion Fairfax and Richard Willis. Rupert Hughes served as President throughout most of its existence. The O’Connor collection at the WGF contains play and event programs from 1921-1935 as well as administrative documents related to the financials and administration of the club.

Screen Writers’ Guild Goes Dark

After the initial momentum that propelled its birth, Guild work slowed due to a confluence of external circumstances. By 1927 the Guild had fallen all but dormant and would remain so until 1933.

In January of 1927 Louis B. Mayer founded the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in part to stop what he and other studio bosses saw as increasing steam in the move toward Hollywood unionization. He convened 36 actors, directors, writers, technicians, and producers to form the Academy. Frank Woods was one of the six writers invited. The Academy positioned itself as well suited to manage relations between talent and studios and arbitrate conflicts, but history has painted it as a company union, designed to stall the progress of other labor organization efforts. Screenwriters and actors, many of whom belonged to Actors’ Equity, were suspicious. Membership was by invitation only, for “distinguished” talent.

Text from a New Years Eve Party invitation, held by the Writers on Dec. 31, 1927. Writers were dissatisfied that the promised standard contract had not yet materialized from the Academy’s Writer-Producer committee. From the Mary H. O’Connor Collection.

That summer, producers, led by Adolph Zukor and Paramount, instigated a 10% salary reduction for all non-union labor. The Academy backed this cut but the actors and the writers balked. Five hundred writers, actors and directors met at the Writers’ Club on July 6, 1927 to discuss the wage cut. After threatening labor action and proposing ideas on how to streamline production, the wage cut was rescinded.

Then an Academy committee composed of writers and producers was put in place to create a standard contract. In September 1927, Grant Carpenter, then SWG President, laid out SWG’s goals in the trade magazines, and stressed the need for cooperation with producers over anti-union militancy and suspicion.

In late 1927 Warner Bros. Pictures released The Jazz Singer, bringing lasting changes to the craft and business of movie making. Labor negotiations were postponed while the industry adjusted to the ramifications of sound technology. Then the Great Depression began in earnest and stalled negotiations even further. Though the movie business remained afloat, studios knew that changes had to be made. 1931 saw another salary reduction, again backed by AMPAS.

In 1931 the Academy’s Writers-Producers committee renewed efforts to create a standard contract. The most important points were agreed upon and the "Writer-Producer Code of Practice" was adopted on April 14, 1932, approved by the Academy on April 21, to go into effect on May 1. The code governed freelance writer-producer working relations, established credit guidelines, and elevated the writer position. The Academy also continued to conciliate disputes between producers and writers. Despite reaching an accord, screenwriters still mistrusted AMPAS. They argued that the agreement did not go far enough, and was inconsistently enforced during the economic disruption of the early 1930s, which saw studios leveraged after years of Wall Street investment and declining ticket sales.

Revitalization

It was in the midst of the Great Depression and in this distrustful and uncertain state that on February 3, 1933, ten writers met at Musso and Frank Grill and the back room of Stanley Rose’s Bookshop to discuss revitalizing the dormant Screen Writers' Guild, forming an organization with the teeth necessary to create real change for writers. The men were Kubec Glasmon, Courtney Terrett, Brian Marlow, Lester Cole, Samson Raphaelson, John Howard Lawson, Edwin Justus Mayer, Louis Weitzenkorn, John Bright and Bertram Bloch. They were signifiers of a new guard - none was older than 40 and all had begun their careers in the talkie era. A week later on February 10, an organizing meeting at the Knickerbocker Hotel gathered more than 50 attendees. The leaders explained the nine principles they had outlined the week before. Lawson, Cole and Bright would later be called out by the House Un-American Activities Committee and blacklisted in Hollywood, partially due to their status as Guild founders.

On March 6, newly inaugurated U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt declared a national "bank holiday,” shutting down operations temporarily until Congress could take measures to restructure the financial system. On March 9, studio chiefs, led by Louis B. Mayer, called for a 50% wage cut for 8 weeks for all workers earning more than $50 per week. They cried poverty and expressed the need for cooperation to get through a time of financial distress. The cut did not apply to executives or IATSE workers who had a union contract. The Academy supported the measure and negotiated the terms. On March 10, the Long Beach earthquake struck, at an estimated magnitude of 6.4, a fitting prelude to the seismic disruption about to take place in Hollywood.

Vote count for Screen Writers’ Guild officers, April 6, 1933, as tallied by Tellers Committee chair, James Seymour. Weitzenkorn and Garrett declined nominations in favor of John Howard Lawson as President and Wells Root and John Bright declined in favor of Joseph Mankiewicz as Secretary. SWG Records, 1933-1954.

Guild meetings continued throughout February and March and Hollywood screenwriters were on board. Leaders were more explicitly interested in protecting all writers at all levels, knowing that only a unified front could hold sway over producers. A Hollywood Reporter headline from March 27 summed up the activity after the movement began to pick up steam: “Writers Get Together. Salary cuts bring home the need for protection - rush of new members to the Guild.”

On March 29, 1933, a special meeting of the SWG was held. The members of the Guild present that day were the Guild President Howard J. Green, Jane Murfin, Dudley Nichols, Ralph Block, Alfred Cohn, Frank Woods, Vernon Smith, Oliver H.P. Garrett, and Tom Geraghty. They agreed to engage two attorneys, Ewell D. Moore and Lawrence Beilenson, to draft a new constitution and by-laws for the Guild, along with a new contract to be signed by the members of the new Guild. On April 5, 1933, the completed constitution and by-laws were approved and were to be presented to the general membership of the old Guild the next day at the scheduled Annual Meeting.

Former Screen Writers’ Guild President Mary McCall stated in her 1948 history of these early days that the lawyers “must have worked fast” because the documents were drawn up and approved eight days later. In fact, the effort had begun long before and this revitalization was able to get off the ground so quickly partially because tracks had been laid starting in 1920.

On April 6, the Annual Meeting of the Screen Writers' Guild was held at the Writers' Club, with Howard J. Green presiding. John Howard Lawson was elected President by acclamation. Louis Weitzenkorn and Oliver H.P. Garrett declined their nominations in favor of Lawson as the perceived middle-of-the-road candidate who could unite screenwriters of all levels and economic circumstances. Frances Marion was elected Vice President, Joseph Mankiewicz, Secretary, and Ralph Block, Treasurer. A contract between members, calling for the drawing up of a Code of Working Rules, and the new Constitution and By-Laws were unanimously adopted. April 6, 1933 became the birthday of the new, reorganized Guild.

A meeting of the new Board on April 7 passed a resolution providing that any writer who had paid (or promised to pay) the necessary $100 and signed the April 6 contract automatically became a member of the Guild. There were 173 charter members.

The Screen Writers’ Guild proved to be a model for the other creative talent unions. Actors, many of whom belonged to Equity, had begun their own meetings in March 1933 and joined in the fight for unionization. Laurence Beilenson, SWG lawyer, would go on to serve as legal advisor during the founding of the Screen Actors Guild (founded 1933), the Screen Directors Guild (1936), and the American Federation of Radio Artists (1937).

SAG was incorporated in June 1933 and remained closely aligned with the Screen Writers' Guild for several years. They jointly published Screen Guilds’ Magazine from 1934-1936. In August 1933, John Howard Lawson called upon his fellow Guild members to resign from the Academy in protest of its handling of the 50% pay cut proposal. Later that year, inspired by writers, many actors resigned from the Academy too.

Recognition

With new life breathed into the Screen Writers’ Guild, the hard work was just beginning. Now the Guild was an organization of all screenwriters joined together in the pursuit of shared goals, based in the center of the film industry. The Guild would face further battles for its life throughout the next decade and work tirelessly for the long-sought standard contract. A rival union sympathetic to the studios, the Screen Playwrights, almost led to the demise of SWG in 1935 and 1936. By 1938, the newly created National Labor Relations Board had intervened and SWG won the membership vote to be the sole collective bargaining agent for writers in Hollywood. Producers would not recognize this role until 1939. Writers and producers finally reached a deal on a Minimum Basic Agreement in 1941, and signed it in 1942. These victories were hard-won and point to the power of unity and the resolve of writers, especially in times of struggle. The Writers Guild of America is a strong union today because of the foundation built by those who championed and defended the screenwriting profession, starting one hundred years ago.

A Selection of Further Reading

Banks, Miranda. The Writers: A History of American Screenwriters and Their Guild. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2015

Ceplair, Larry and Steven Englund. The Inquisition in Hollywood: Politics in the Film Community 1930-1960. Garden City, N.Y.: Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1980.

Cole, Lester. Hollywood Red: The Autobiography of Lester Cole. Palo Alto: Ramparts Press, 1981.

Hamilton, Ian. Writers in Hollywood 1915-1951. New York: Harper & Row, 1990.

McCall Jr., Mary C. “A Brief History of the Guild.” The Screen Writer 3, no. 11 (1948): 25-31.

Ross, Murray. Stars and Strikes: Unionization of Hollywood. New York: Columbia University Press, 1941.

Schwartz, Nancy Lynn. The Hollywood Writers’ Wars. New York: McGraw Hill, 1982.

Wheaton, Christopher. “The Screen Writers’ Guild (1920-1942): The Writers’ Quest for a Freely Negotiated Basic Agreement." PhD. diss. University of Southern California, 1973. USC Digital Library. Web. 30 July 2020.

Media History Digital Library contains countless digitized motion picture trade and fan publications, integral to studying early Hollywood history.