WRITING YOUR SCREENPLAY WHILE SOCIAL DISTANCING: TEXT ON SCREEN

This post is inspired by one of the great questions we get in the library from time to time. That question is,

“How do I format a text message conversation within my script?”

Patrons come to us looking for examples of how to describe a character sending texts, writing e-mails and letters, passing notes, reading sign posts, scanning websites and more.

So much of our communication in the digital/information/pandemic age is, in fact, written. To bring this written communication into your film and TV writing is to effectively hold the mirror up to the times in which we live.

While conventions for formatting dialogue, description, montages, etc. are well-established, rules for formatting written text on screen are more ambiguous. Sometimes it’s easier to ditch the jargon, especially if you have lots of instances of texting or signage. Basically, you only have so many uses of the word “SUPER” or “CHYRON” before a reader heaves an exasperated sigh.

So what do you do? Writers across genres and styles approach it differently. In the interest of providing lots of ideas and inspiration (and because this topic is more technical), this post will be example-heavy rather than loaded with commentary.

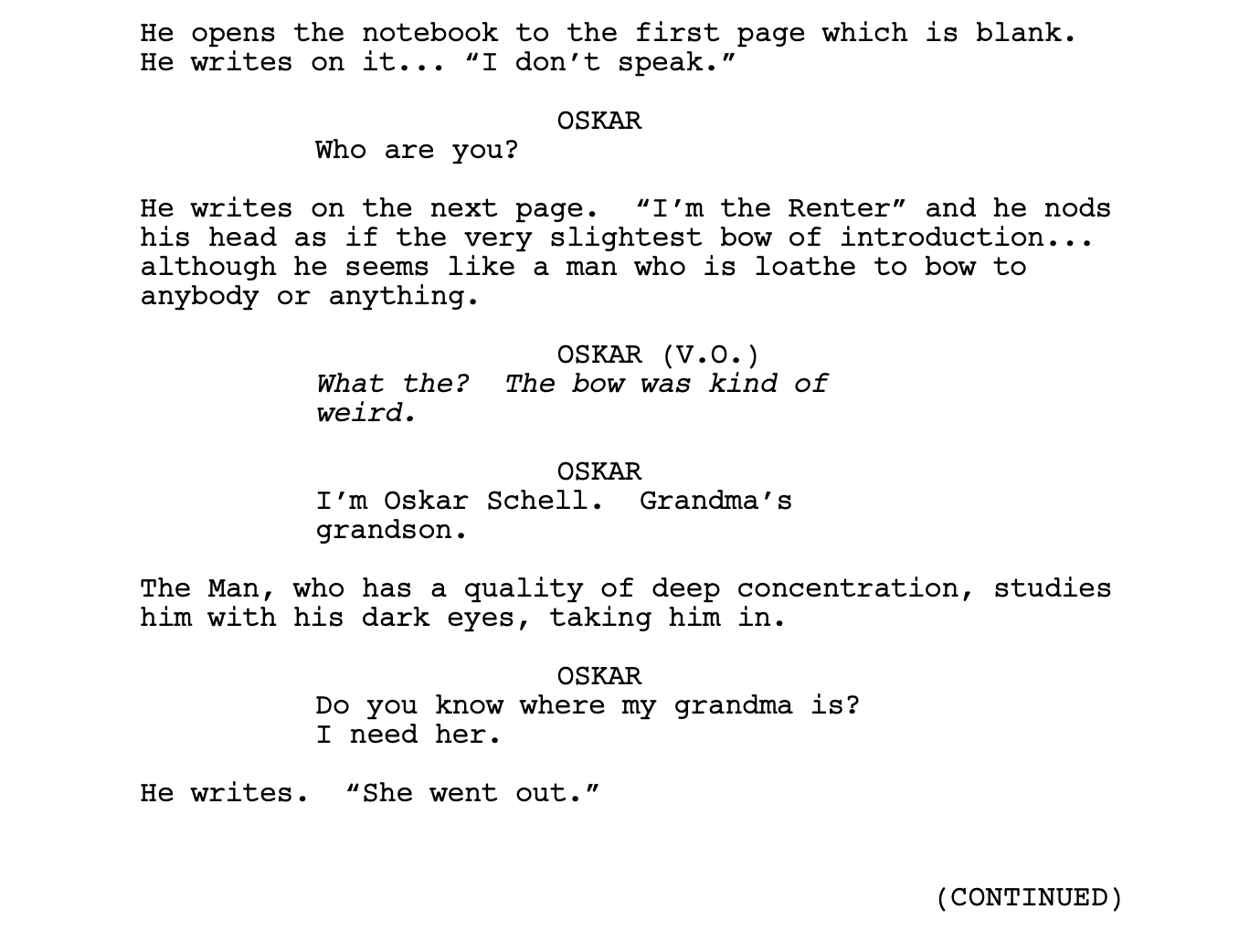

EXTREMELY LOUD & INCREDIBLY CLOSE (2011)

Screenplay by Eric Roth

Based on the novel by Jonathan Safran Foer

The character of the Renter doesn’t speak, but rather communicates by writing statements onto a notepad. Roth inserts the Renter’s “speech” into the description of what we see, using quotations.

FRUITVALE STATION (2013)

Written by Ryan Coogler

Coogler, in this script, formats text message conversations just like dialogue adding “TO” and “FROM” to the character names and CAPITALIZING the text so that it stands out in the reader’s mind as written rather than spoken.

HARRY POTTER AND THE CHAMBER OF SECRETS (2002)

Screenplay by Steve Kloves

Based on the novel by J. K. Rowling

Kloves takes a direct and literary approach in adapting how Harry writes and receives responses in Tom Riddle’s diary. Note the use of colons before somebody writes or speaks as well as the bolding and italicizing of the written text we see on screen.

THE HOLIDAY (2006)

Written by Nancy Meyers

Meyers formats the messages exchanged between the two characters much like the formatting of a conversation on AOL Instant Messenger. This way the reader can easily distinguish between the written messages and the spoken dialogue. Note the CAPITALIZING of character names (much like dialogue) as well as the verbs used before the colons, which helps to keep the description active.

MEMENTO (2000)

Screenplay by Christopher Nolan

Based on a story by Jonathan Nolan

Memento features a lot of on-screen written text, notably tattooed all over the main character’s body. Here, we find written text on the back of a photograph, which Nolan CAPITALIZES and puts into quotations.

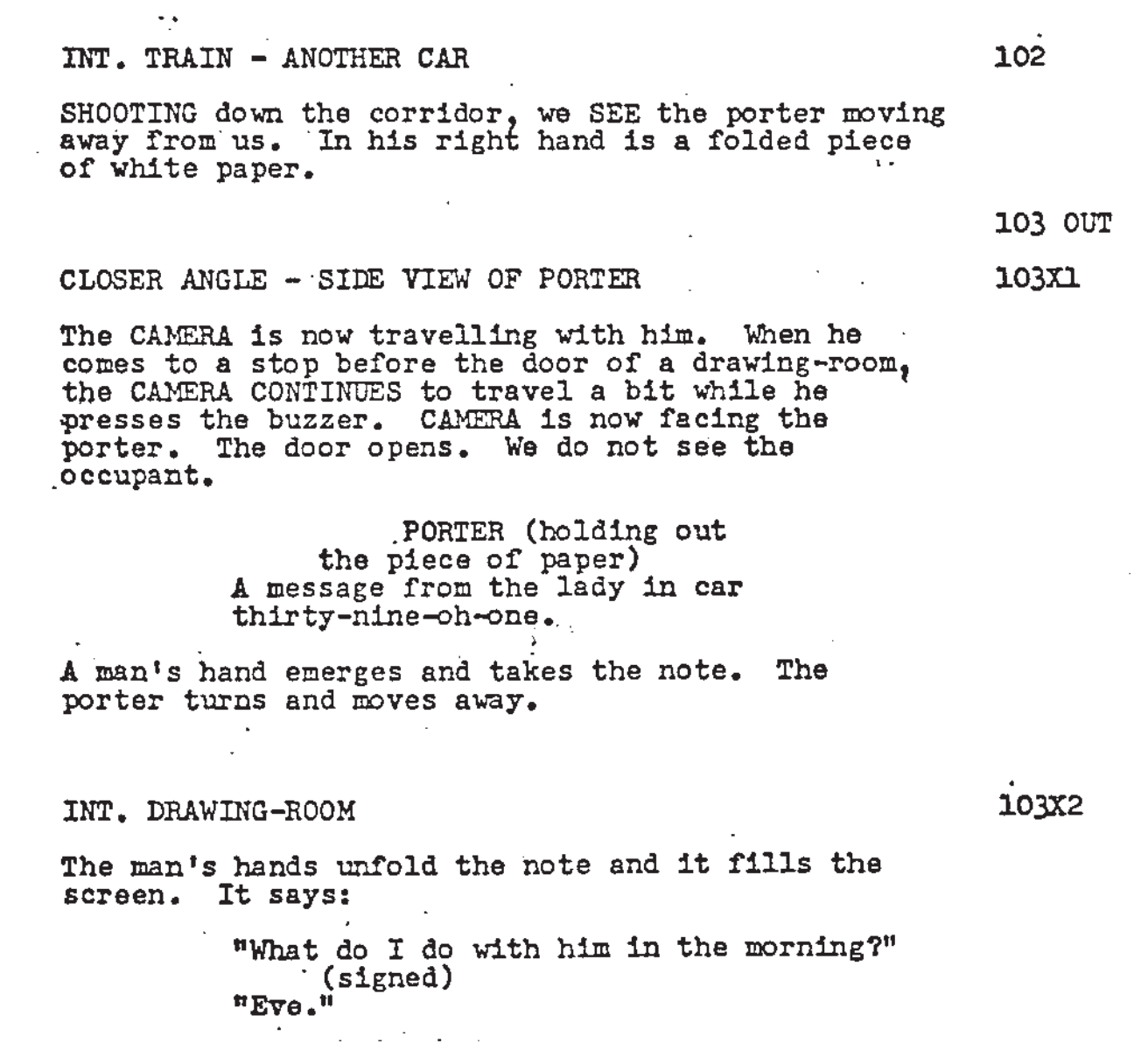

NORTH BY NORTHWEST (1959)

Written by Ernest Lehman

This moment in North by Northwest is discussed most often as a shrewd, unexpected turn of events, but we thought it might be fun to show how the note, “What do I do with him in the morning?” is formatted.

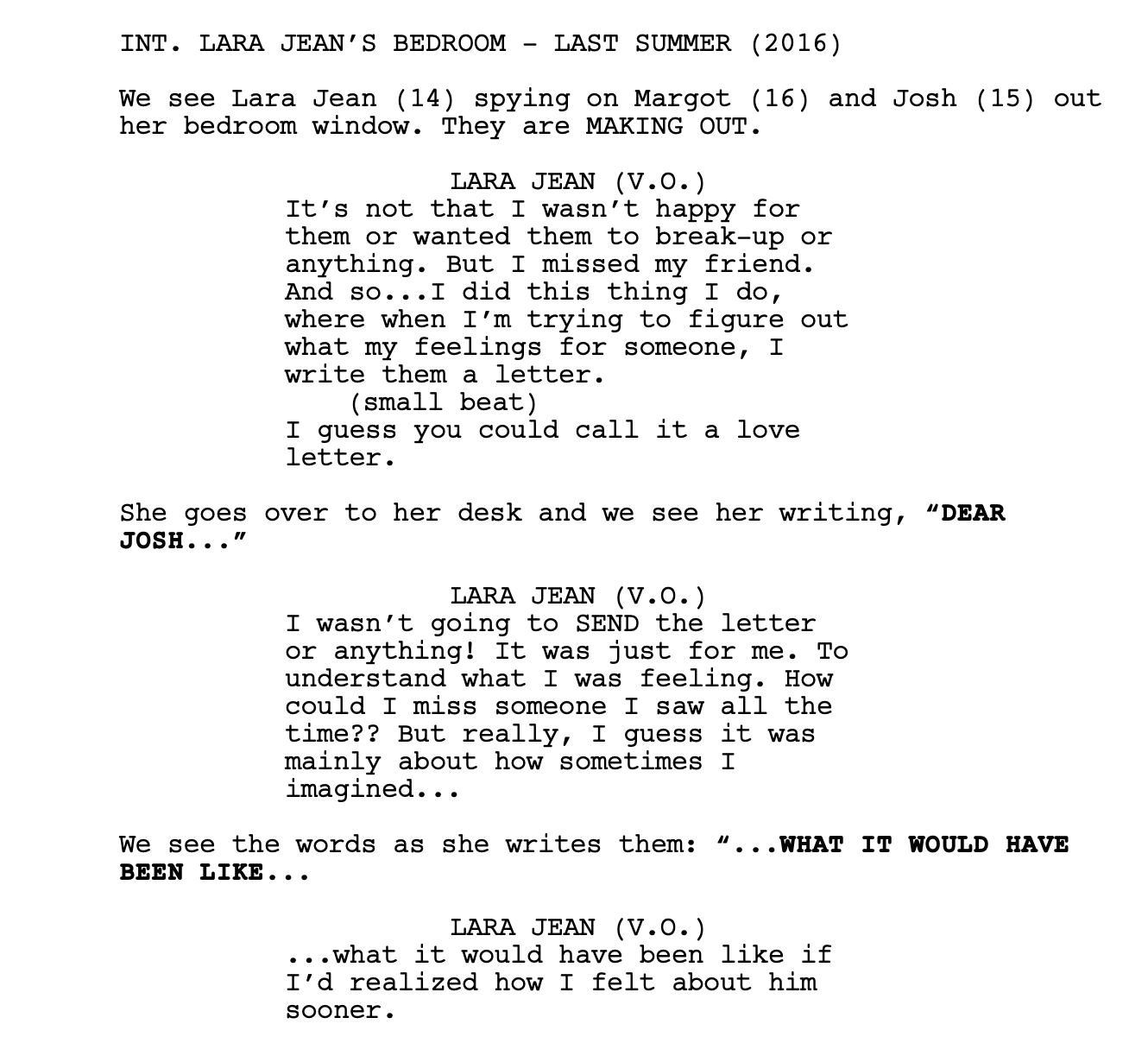

TO ALL THE BOYS I’VE LOVED BEFORE (2018)

Screenplay by Sofia Alvarez

Based on the book By Jenny Han

Here we have a character sitting down to write a letter. Alvarez keeps the description simple, but specifies the written text we see on screen by CAPITALIZING it, bolding it and putting it into quotations.

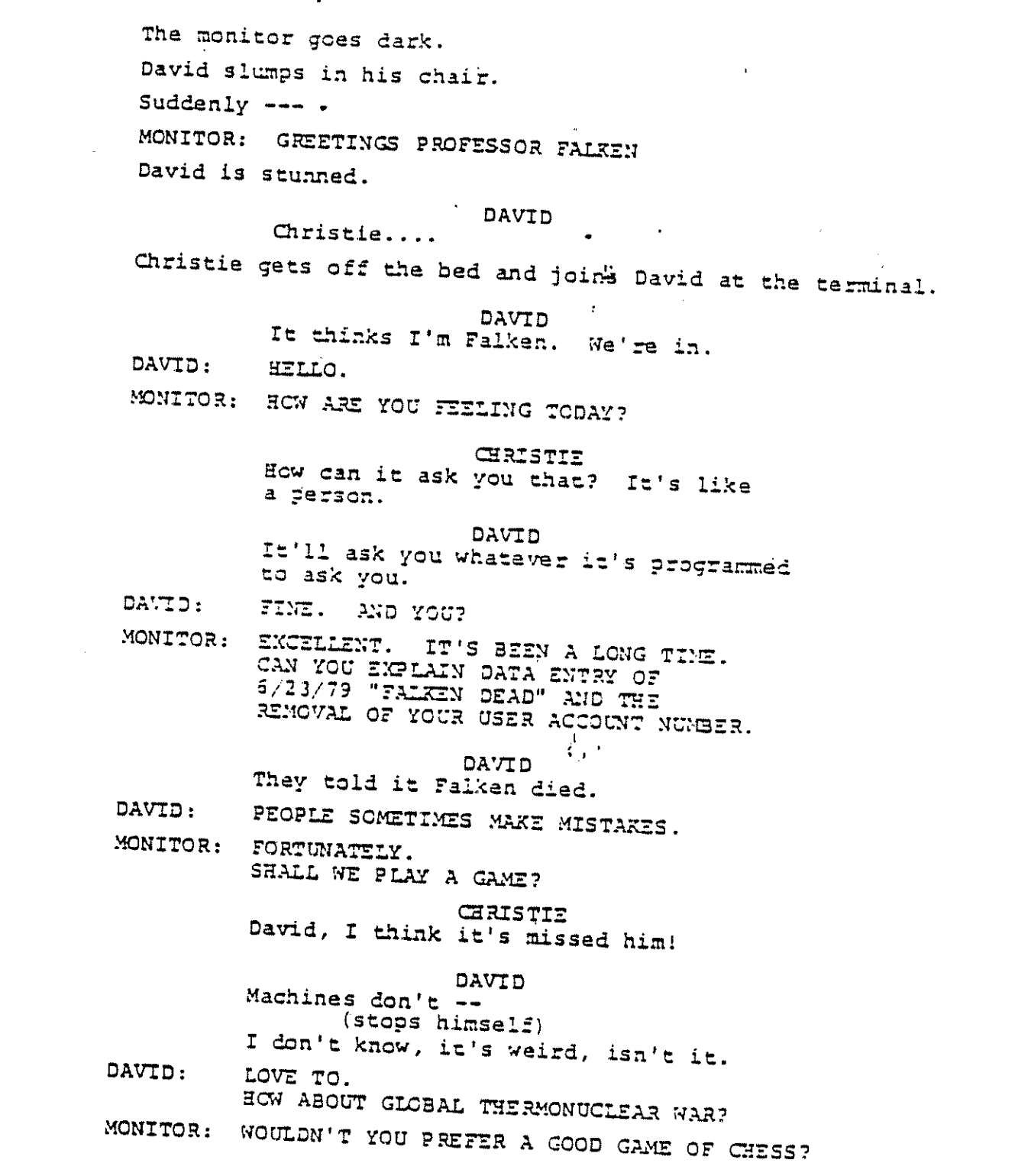

WARGAMES (1983)

Written by Lawrence Lasker & Walter F. Parkes

The written exchange between David and the computer is formatted exactly as we would watch it unfold on the monitor (CAPITALIZATION included). As in The Holiday, the formatting helps the reader distinguish between the seen/written text and the spoken dialogue as they happen concurrently.

WILD (2014)

Screenplay by Nick Hornby

Based upon the book by Cheryl Strayed

Note that Hornby doesn’t use the word “SUPER” but rather simply explains how we see the text Cheryl writes in the book almost like a superimposed title. After establishing this, less explanation/description is required when more written text appears on screen.

As you can see from these examples, there are a handful of different ways to approach text on screen. For questions and more elaboration on this or any other topic related to film and TV writing during the pandemic, send an e-mail to library@wgfoundation.org and we can try to help.

Happy writing!