WRITING YOUR SCREENPLAY WHILE SOCIAL DISTANCING: MUSIC AND MUSICAL NUMBERS

To include the lyrics or not to include the lyrics?

If you’re writing a script that features a song or musical number, that is the question.

Eventually, there will come a moment in something you write where it feels natural for the characters to sing or dance. When this happens, how do you approach formatting and description, especially if the script is NOT a musical? If the script IS a full-blown musical where the characters burst into song at every turn, how do you format that?

These questions come up often and we in the library love to offer our insights. This week, we thought it might be helpful to unpack some musical numbers from popular films. We’ll also throw in some examples from TV shows.

Before we get started, let’s make a vital distinction. A bunch of rock stars, roadies, and groupies sitting on a tour bus singing “Tiny Dancer” is very, very different from Julie Andrews twirling around on a hill belting to the trees and birds. The solitary moment in your rom-com where the characters hear a favorite tune in the bar and start wailing is different from a movie adapted from a stage musical where the music and lyrics develop character and push the story forward. In one scenario, lyrics aren’t all that important. In the other, they’re imperative. Then, we meet the musical biopic, where numbers usually occur naturally, but still FEEL like a musical. It can be tough to figure out what to do and there aren’t always easy answers.

This blog post should enrich your approach to including song/dance/music in your script, noting how to make it feel as innate, or as magically innate, as possible. We love Singin’ in the Rain and The Wizard of Oz, but we’ll keep our examples contemporary because the formatting in those movies can come off somewhat dated on the page.

It’s also wise to give thought from the outset: Are you the lyricist? Are you working with a lyricist? Are you borrowing a popular song for this moment in your script? There will be rights considerations as your script lurches closer to sale/production. It’s too much to dive into in this technical blog post, but still an essential concern. For now, let these scripts be your guide and write.

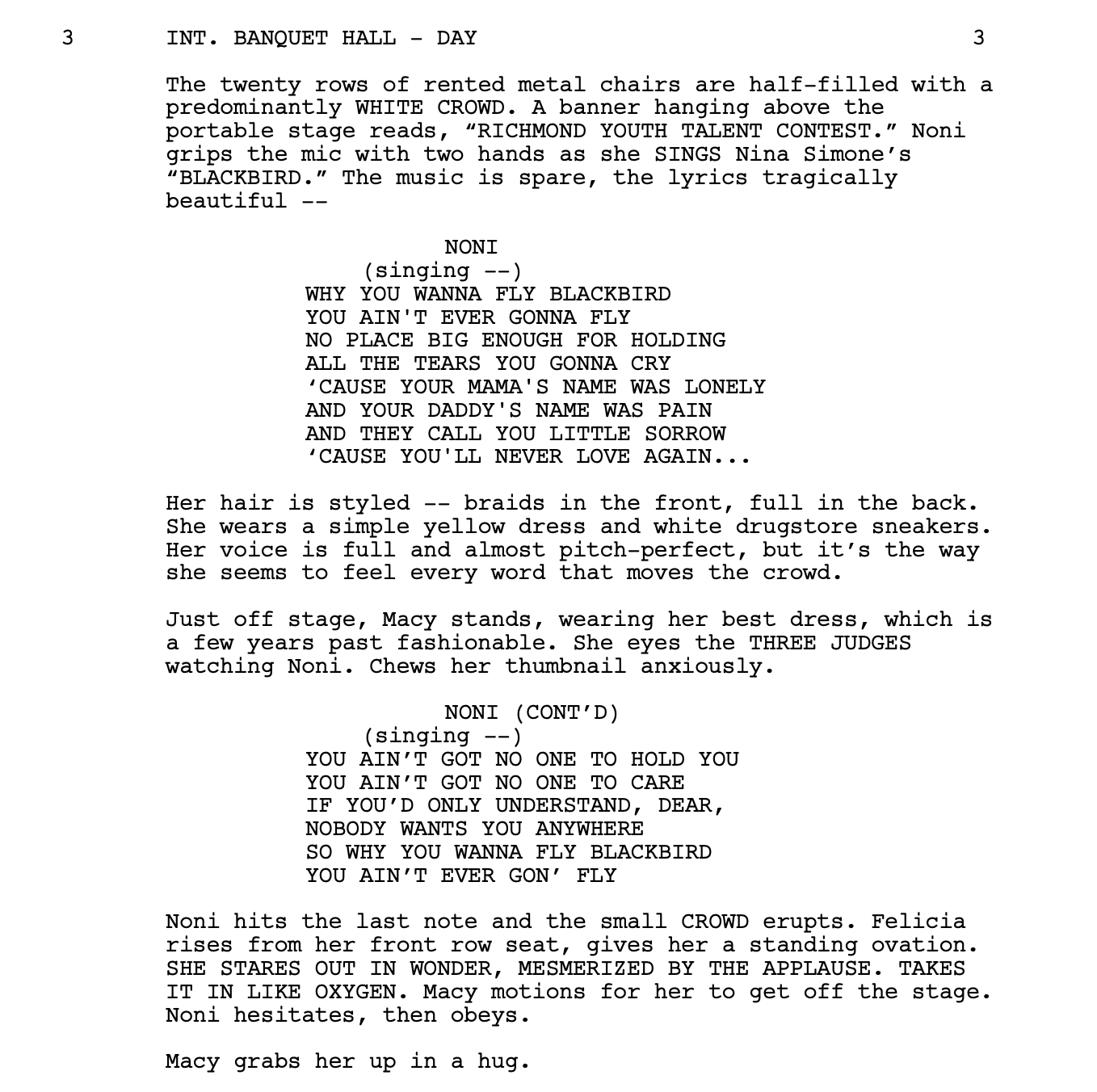

BEYOND THE LIGHTS (2014)

Written and Directed by Gina Prince-Bythewood

This is a fictional story done loosely in the style of a musical biopic. In this song performance, the Nina Simone lyrics are important to the story and to the feeling of the moment, so Prince-Bythewood includes them in the script.

Note: Lyrics are typically CAPITALIZED or italicized or both, so the reader and eventual production team can differentiate singing from dialogue.

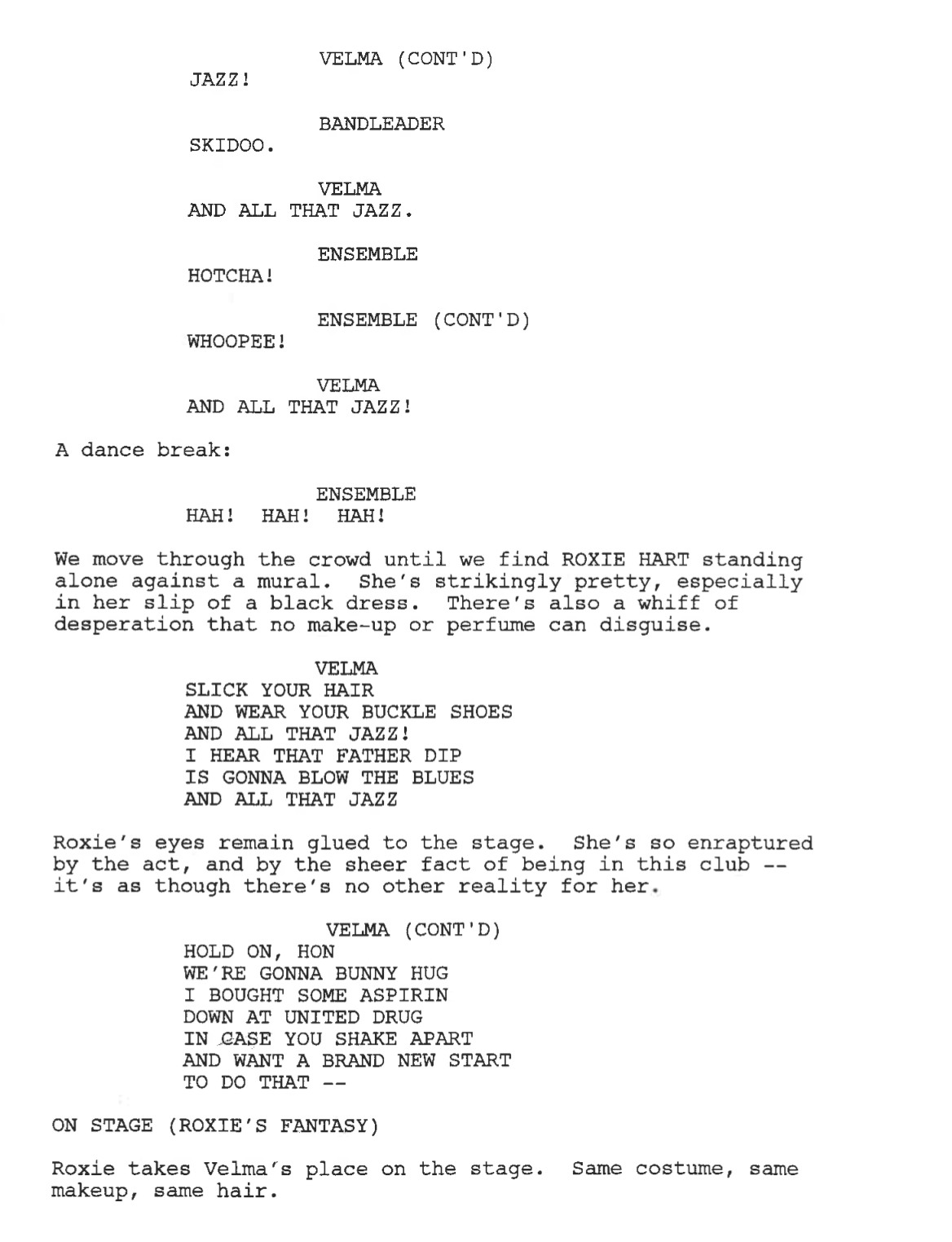

CHICAGO (2002)

Screenplay by Bill Condon

Based on the musical play by Maurine Dallas Watkins and book of the musical play by Bob Fosse and Fred Ebb Music by John Kander and Lyrics by Fred Ebb

Sometimes audiences watching movies based on musicals gripe that, “People don’t just burst into song! It doesn’t feel natural!” In writing a musical (or adapting one) for the screen, one way to ensure that a song feels natural is to establish that the number is taking place inside a character’s head. Another way is to establish that the number takes place on a stage or in another setting where people frequently sing or perform. “All That Jazz” — the first number in Chicago — does both. Velma Kelly performs in a nightclub and Roxie Hart watches — later imagining herself performing that same number. Establishing right up front that all numbers take place in Roxie’s showbiz-obsessed head, the filmmakers ensure that no musical moment feels weird or inorganic.

So, if you’re writing a screen musical, the audience begs you to establish how the musical numbers will work from the outset.

Note: Lyrics are CAPITALIZED.

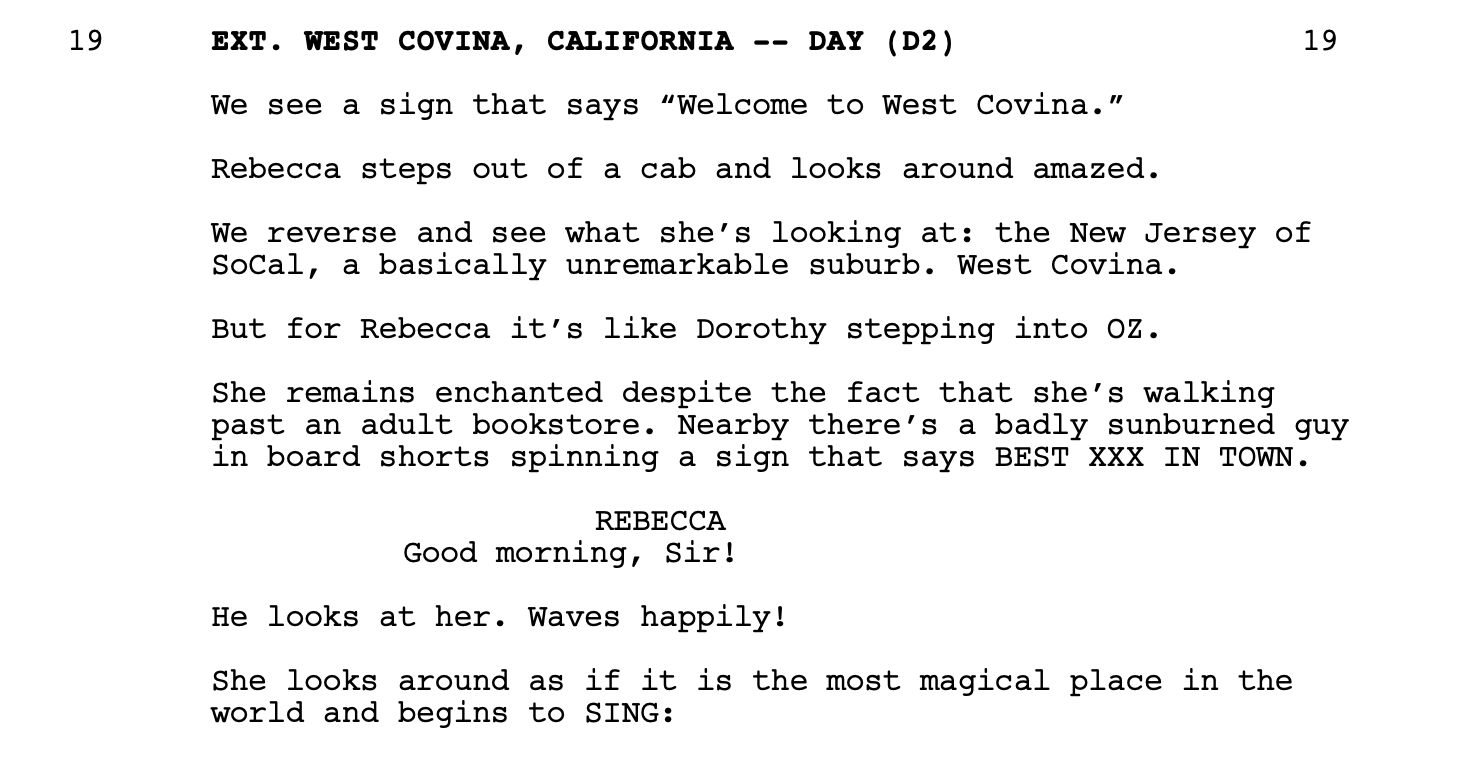

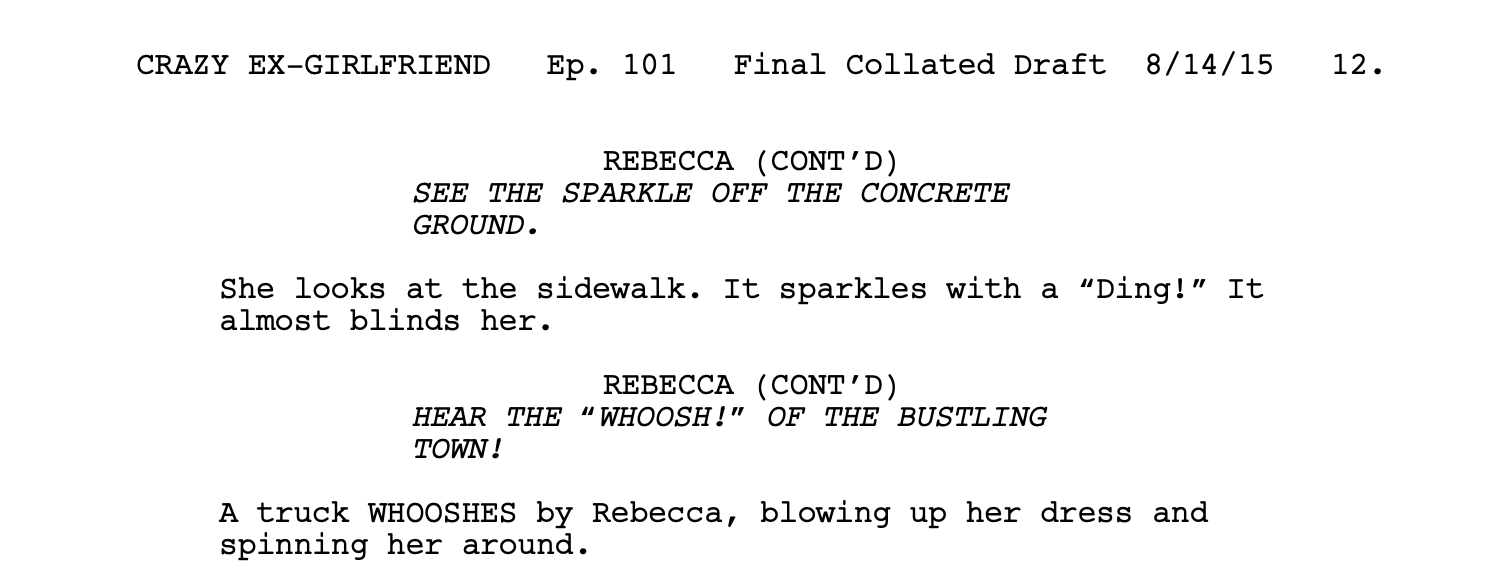

CRAZY EX-GIRLFRIEND (2015)

“Josh Just Happens to Live Here!” (Pilot) 1-1

Written by Rachel Bloom & Aline Brosh McKenna

Here is an example from a TV series that operates a lot like Chicago with musical numbers emanating mostly from the protagonist’s mind. The writers ground this number in Rebecca’s point-of-view by explaining she feels like Dorothy stepping into Oz.

The number’s comedy and magic are generated from the contrast. West Covina is NOT Oz. Think: Gene Kelly happily dancing and splashing around in bad weather. Contrast between feeling and setting can really lift a number.

Note: Lyrics are CAPITALIZED and italicized.

GLEE (2009)

“Wheels” 1-9

Written by Ryan Murphy

This musical number feels natural in that it’s performed by students in a show choir, rehearsing on a stage. It’s an example of how description of a song or musical sequence can be sparse, but also get the point of across. This is a great moment to look at if you’re hoping to casually describe a song moment in your script, but don’t necessarily want to include the lyrics.

But if you do include lyrics, note that here they’re italicized and in quotes.

THE LITTLE MERMAID (1989)

Written by John Musker & Ron Clements

Songs by Howard Ashman & Alan Menken

Musical storytelling has always found a natural fit with animated films. Perhaps it’s because we often equate a person’s singing/music with their having a soul. Musical numbers help us to be moved by hand or computer-rendered drawings, interpreting them as sentient and real.

“Part of Your World” is a classic “I Want” song. This type of song/storytelling device is borrowed directly from Broadway musicals, helping the audience to know exactly what the main character wants, to empathize with that want and hope for the character to get it.

Note: Lyrics are CAPITALIZED.

ROCKETMAN (2019)

Written by Lee Hall

Here’s an example of a musical number in a biopic. To be specific, it’s Elton John’s first time performing at the Troubadour — a significant turning point in his career. We’re including this example as it effectively weaves description of the performance itself with a touch of magical realism, which heightens the emotional feeling of the number.

Note: Lyrics are italicized.

SCHOOL OF ROCK (2003)

Written by Mike White

This moment gives one an idea of how to format a diegetic song, or one that occurs within the action or context of the everyday. Dewey, the substitute teacher, explains multiplication to his class by singing a song.

Note: Lyrics are italicized and also note the “(singing)” parenthetical.

In this blog post, we didn’t include any examples without lyrics. Hopefully, even if you choose not to include lyrics in your script, you now have an idea of the kind of verbiage that goes into describing a musical moment. If you have questions about this topic or about other scripts, feel free to e-mail the WGF Library staff at library@wgfoundation.org.

Until next time, happy writing!