WRITING YOUR SCREENPLAY WHILE SOCIAL DISTANCING: BACKSTORY AND EXPOSITION

Exposition is tricky to employ in feature screenplays, but make no mistake about it:

When it comes to character, exposition is the secret sauce.

Let’s call it “revelation of character” rather than exposition. When done well, revelation of character often produces some of the most intriguing and memorable moments in a film.

Note the sensation we chose to lead with here: Intrigue.

When we watch movies (or TV shows or any visual storytelling medium), we don’t like to be bopped over the head with all we need to know about a character. We like to be intrigued.

We want clues, nuggets and hints that we then piece together in our heads. Just because film is a SHOW ME medium doesn’t mean it’s a SHOW ME EVERYTHING medium.

Characters are like bread. Nay! Cheese. Give us a small nibble and that little nibble will trigger dopamine in our brains. We’ll be excited by the flavor. We’ll want to devour more! But give us the whole block and we probably won’t be able to digest it.

To put it less metaphorically: None of us walk around with emotional X-ray vision. None of us can see every little thing that’s happened… every belief, feeling or affliction that lives within every person that we meet. However, if we’re paying attention, people occasionally drop subliminal hints. When we get that hint or that clue, suddenly with this newfound knowledge, we’re afraid to encounter this person again or we can’t wait to know more about them or we eagerly anticipate what this person will do next.

Good revelation of character is the secret (cheesy) sauce.

Exposition, of course, applies to more than just character. Exposition can also apply to the world, culture or time period in which the story takes place. A story can be derailed by too much expository information and confusing with too little. What information do you share? How much of it do you share? How much should you assume your audience knows or does not know going in?

This blog post will focus exclusively on character exposition and backstory. This is because characters are the vehicle for everything else. If you reveal your characters in an intriguing way, everything else should (theoretically) follow.

CASABLANCA (1942)

Screenplay by Julius J. Epstein & Philip G. Epstein and Howard Koch

Based on the play “Everybody Comes to Rick's” by Murray Burnett and Joan Alison

This moment in Casablanca utilizes two effective techniques. First, Rick looks up at that plane and we know it’s causing him anguish and we can’t help leaning in to wonder…. Why?

Then, Renault speculates about Rick’s past life and activities, inviting speculation from us as readers too. It’s always good to remember that if a reader or audience is speculating, they’re actively participating in your story.

COCO (2017)

Original Story by Lee Unkrich, Jason Katz, Matthew Aldrich, Adrian Molina

Screenplay by Adrian Molina and Matthew Aldrich

Chicharrón could simply say, “No,” when Héctor shows up too borrow his guitar. In telling him he doesn’t want to see his “stupid face” and reminding him of things he’s borrowed and failed to return, Chicharrón explains to us that Héctor is a bum.

The exposition is used as ammo in the push/pull of the scene. Plus, we FEEL FOR Héctor who is clearly down on his luck.

THE DEVIL WEARS PRADA (2006)

Screenplay by Aline Brosh McKenna

Based on the novel by Lauren Weisberger

If you want to get the rules of a world across smoothly, a great technique is to make one character a fish out of water to whom the other characters must constantly explain everything. Here, the fish is Andy.

Note how all the details about how to prepare the office and work for Miranda add a total fearsomeness and deep dread (i.e. - gleeful anticipation) of her when she’s not even in the scene.

From Emily’s overzealous explanation, we also get a sense of her superiority complex AND how the Paris trip means everything to her. Both setups come into play later.

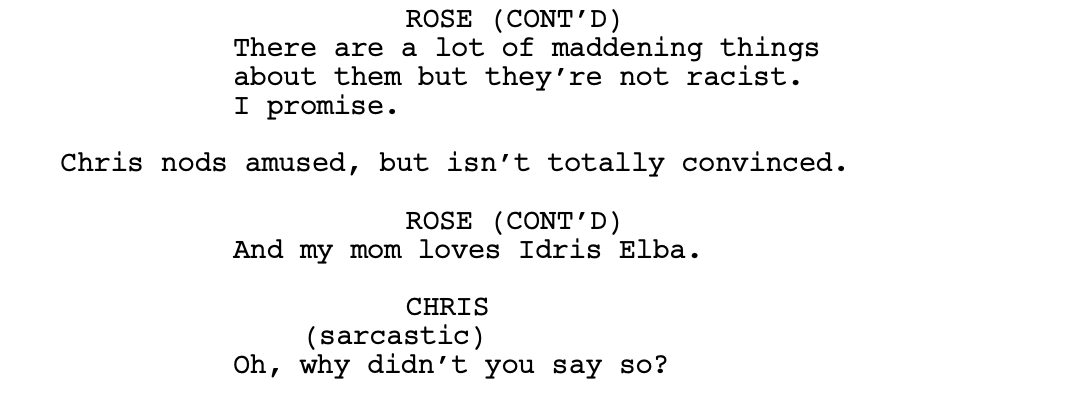

GET OUT (2017)

Written by Jordan Peele

Just like The Devil Wears Prada, having characters talk and share information with each other — in this case, about Rose’s parents — creates a sense of expectation/anticipation around meeting them.

From this conversation, in any scenes with Rose’s parents, as a reader or audience, we look for signs of racism or lack thereof, which puts us in an engaged and active position.

It also helps us to contemplate the nature of racism, which is the underlying theme of the movie.

GIRL, INTERRUPTED (1999)

Screenplay by James Mangold and Lisa Loomer and Anna Hamilton Phelan

Based on the book by Susanna Kaysen

In this case, the writers need to get information to us — the audience — about the psychological conditions afflicting these hospital residents. How do they facilitate this? Susannah overhears her psychiatrist mention “Borderline Personality Disorder” to her parents, so to help her understand her diagnosis, the other hospital patients break into the doctor’s office where they all read their individual files.

The writers make psychological terms and jargon dynamic by having the patients switch files with one another and read them aloud (with commentary).

HAROLD AND MAUDE (1971)

Written by Colin Higgins

Maude is wise, sweet and unflinchingly optimistic, even in the face of great sadness. We all know what concentration camp inmate tattoos look like (and have thousands of pictures and associations of concentration camps in our head). In one tiny visual we learn more than Maude could explain to us in a 1000-word monologue. This is what we mean when we describe film as a “show me” medium.

HOME ALONE (1990)

Written by John Hughes

All you need to know is that Fuller wets the bed and that Linnie is a brat who feels the need to remind Kevin that Fuller wets the bed.

Little splashes of detail can be wonderfully evocative in giving a sense of character. As illustrated time and again in this and other blog posts, less is often more.

WONDER WOMAN (2017)

Screenplay by Allan Heinberg

Story by Zack Snyder & Allan Heinberg and Jason Fuchs

The ultimate way to learn about character is to observe what someone does in a jam. Exposition is thrilling when in a moment of crisis, a character does something unlikely and surprises even themself.

Happy New Year, writers! If you have questions about exposition or about other topics or scripts, feel free to e-mail the WGF Library staff at library@wgfoundation.org.

Until next time, happy writing!